AI and Deming's Theory of Knowledge

What a Recent Paper Tells Us About How We Learn Better Than AI (for now...)

Edit: I’ve added a paragraph to expand on why LLMs currently can’t reason and test hypotheses like humans due to a lack of metacognition. See here.

THE AIM for this newsletter is to share the results of an experiment that pitted humans against Large Language Model AI agents in a contest to evaluate reasoning and novel problem-solving capabilities that are consistent with what Deming taught in The New Economics about we learn and acquire knowledge . It comes courtesy of a paper I came across by Warrier and colleagues (of Harvard, Université de Montréal, Cambridge, MIT, and Cornell) called “Benchmarking World-Model Learning” published on October 22, 2025.

Within, the authors describe how they developed a new method for testing three “frontier” LLM AI Agents (Anthropic's Claude.ai, OpenAI’s o3, and Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro) using a learning assessment framework they created called WorldTest, and a complementary implementation called AutumnBench to run a series of 129 challenges for the agents and a panel of 517 screened human participants. What they learned explains just how far AI has to go to match human intelligence.

Let’s dive in to learn more…

tl;dr: Humans Win

If you’ve used any of the most popular AI platforms, this won’t come as too much of a surprise, particularly if you’re versed in Dr. Deming’s Theory of Knowledge domain of his System of Profound Knowledge: the human participants outperformed their AI agent counterparts across all tasks due to their consistently demonstrated ability to learn about an environment or world through continual experimentation, then apply that learning to a task or challenge. Moreover, they took considerable advantage of a “reset” feature to restore the simulated environment to “factory settings” to test hypotheses about how things worked updating their beliefs as they went. In contrast, the AI models would just brute-force their way through without any adjustments to their prior beliefs.

In short: the humans succeeded because they were efficient scientists who would strategically test hypotheses and update their beliefs and models accordingly, what Dr. Deming would immediately recognize as aligned with the Theory of Knowledge (ie. testing predictions) domain of his System of Profound Knowledge, something the AI models in their current iterations could not.

World-Test and Autumn Bench

The original aim for the research presented in the paper was to develop a more effective way to test AI reasoning capabilities outside of overly-restrictive and prescriptive single-focus tasks and challenges. What they were seeking to understand was how well the models could freely gather information about an environment to learn how it works, then apply that knowledge to a range of challenges in that environment.

To do this, they first created a behavioural framework (WorldTest) to evaluate how well an agent can interact with the model of an environment without constraining how the agent represents it internally or in response to rewards. WorldTest evaluates AI agents in two phases:

Interaction: where the agent can freely explore and interact with its environment free of constraints or rewards. It can also “reset” the environment to an initial state to test hypotheses and facilitate systematic exploration.

Test: where the agent is presented a challenge environment that may have one or more changes in states, transitions, or actions. Within this they attempt to complete a task to evaluate if they can apply what was learned during the Interaction phase. Rewards and goals are introduced to direct the agent behavior.

Think of WorldTest this way: your teacher or professor springs a pop-quiz on you, but to have a bit of fun he gives you unsupervised time to study and experiment with solving a novel problem, then he presents you with a test to evaluate your ability to apply, not memorize, what you learned. WorldTest is the method and rules for running these kinds of tests.

In total, the researchers created 129 unique problems that were spread across 43 environments and 3 types or categories of tasks the AI had to perform. These were written in a language called AutumnBench, which itself is an instantiation or implementation of the rules framework, WorldTest, so it automatically presents and runs the challenges in two phases as described.

Task Categories

Researchers next devised three types of tasks to evaluate AI agent performance:

Masked Frame Prediction (MFP) that test the agent’s ability to predict unobserved states or outcomes based on its understanding of how the simulated world works. Ex: predicting how long a covered pot will take to finish cooking a type of meal based solely on what you can observe without lifting the lid.

Planning (PL) that test the agent’s ability to estimate immediate and deferred consequences from actions in the simulated world, then generate a series of actions to reach a desired state. Ex: planning the sequence of steps to complete a recipe based on a learned model of a kitchen.

Change Detection (CD) that test the agent’s ability to detect and adapt to changes in the simulated world’s rules. Ex: recognizing and adapting to an unfamiliar kitchen to find the utensils, operate the appliances, locate the ingredients.

The simulated environments for the tests were themselves designed to be structurally novel, intuitive to humans, and diverse in their world dynamics and learning mechanisms. They included physical simulations, emergent systems, multi-agent dynamics, abstract logic environments, game-inspired scenarios, and tool usage.

For the 517 human participants, the challenges played out using a web UI that could be manipulated with a mouse while the AI Agents were given a text-based interface.

What Happened?

Overwhelmingly, the human participants outperformed their AI counterparts across all environments and task types, achieving near-optimal scores, while the LLMs frequently failed. Three traits separated humans from machines:

More efficient learning about the world model and how it behaved;

Superior experimental design using the “reset” feature to test hypotheses;

Updating and their beliefs to integrate contradictory evidence.

In particular, the human participants excelled in converting what they learned during the Interaction Phase into strategies and actions for solving the various challenges, while their AI counterparts would frequently fail at #3, especially with Masked-Frame Prediction (MFP) challenges, preferring to fall back to their originally-learned rules.

In other words, AI would routinely fail the professor’s pop-quiz…

What’s the Deming View?

When I first read this paper I was immediately struck by how well the researchers’ observations of the human participants’ performance aligned with Dr. Deming’s view on how we acquire knowledge through theory. In The New Economics, he writes:

Knowledge is built on theory. The theory of knowledge teaches us that a statement, if it conveys knowledge, predicts future outcome, with the risk of being wrong, and that it fits without failure observations of the past.

Rational prediction requires theory that builds knowledge through systematic revision and extension of theory based on comparison of prediction with observation…

Theory is a window into the world. Theory leads to prediction. Without prediction, experience and examples teach nothing.

(2nd Ed, pp. 102-103 , 3rd Ed, pp. 69-70 )

Human participants demonstrated this to significant effect by using the “reset” feature during the Interaction Phase to test a range of predictions (hypotheses) about how the world worked, updating their prior-held beliefs as the old theories failed. Again, Dr. Deming observed this as well:

No number of examples establishes a theory, yet a single unexplained failure of a theory requires modification or even abandonment of the theory.

(2nd Ed, p. 104, 3rd Ed, p. 71 )

Thus, in light of the results of the tests, I think Dr. Deming might say that current AI models fall short in mistaking information for knowledge, which humans can and do trip up on all the time, as well. He also notes:

Information is not knowledge…

To put it another way, information, no matter how complete and speedy, is not knowledge. Knowledge has temporal spread. Knowledge comes from theory. Without theory, there is no way to use the information that comes to us on an instant.

A dictionary contains information, not knowledge. A dictionary is useful. I use a dictionary frequently when at my desk, but the dictionary will not prepare a paragraph or criticize it.

(2nd Ed, p. 106, 3rd Ed, pp. 72-73)

Ergo, by ignoring the “reset” feature, the AI agents demonstrated that they were in dogged pursuit of information about the properties and characteristics of the environments but not in building knowledge from them about how they worked, particularly when disconfirming evidence was presented to them. This is a consequence of how they are programmed, and how they currently fail to emulate a key feature of human intelligence and adaptability, something cognitive scientists call metacognition or the awareness of how we think.

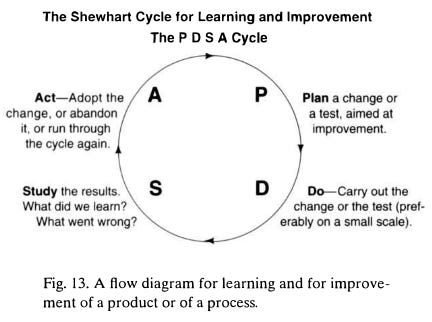

A Possible Remedy: PDSA

Perhaps, were the AI models to be programmed to operationalize the acquisition of knowledge as Dr. Deming recommended, using a PDSA process flow, they may have fared better. Recall that the PDSA or Shewhart Cycle is a systematic method for testing hypotheses to build knowledge from information over time:

In this way, the models might use their Interaction Phase time to conduct multiple PDSAs to learn about the environment, then take that knowledge into the Test Phase to run another series of PDSAs to evaluate their theory of how things work and how best to perform the tasks in the new environment.

The Catch: LLMs Aren’t Designed This Way

As much as this would be a fantastic way to augment an LLM’s reasoning capabilities, it’s actually orthogonal (independent) to how they operate, which is as a predictive pattern matching engine. The researchers’ paper bears this out, showing that LLMs can act like they know or understand things, but cannot learn that they don’t. Humans have the edge here in that they possess metacognition or awareness of their own thinking or learning habits and processes, and this allows them to formulate hypotheses and test them. Just observe children at play and you’ll see this in action.

HOWEVER, this doesn’t mean they will never have this capability. It could be quite possible to wrap an AI Agent with some scaffolding to augment it with persistent memory (to hold learning results), an experiment/feedback algorithm, and a belief updating rule like PDSA to turn it into a linguistic reasoning substrate to implement genuine learning capacity. But… this is well beyond the scope of this newsletter!

Reflection Questions

Consider what the researchers uncovered in their evaluation of AI agent capabilities to learn about simulated environments and apply that learning to novel tasks and challenges.

What implications are there for organizations considering increased use of AI? Have we overestimated current AI model intelligence capabilities to actually learn? Have we confused model training with huge swathes of information for knowledge? Will AI models ever truly learn in the same way as humans?

Would implementing a systematic learning algorithm like PDSA improve outcomes? What would be the main challenges? How could they be overcome?

How do you approach learning in your organization? Is experimentation encouraged or dismissed as wasting time and resources? How is it supported? What processes are followed? Are prior beliefs updating when new contradictory evidence is presented, or is the reflex to double-down?

As always, let me know your thoughts in the comments below!

A great article, thank you. I especially enjoyed how you connected AI’s limitations to Deming’s view of learning through theory.

When the AI hype took off a few years ago, I described it as Fred.Taylor's Wet Dream. The ultimate replacement for those bureaucratic, "efficient" overhead departments that so often get in the way of effectiveness. Where rigid procedures and standards for the sake of standards are far more important than results and quality.

They are great for routine work in closed environments. But that is about it.

So far I have not changed my mind about AI.