New Competency #3: How We Learn, Develop, and Improve

Experience Without Theory Teaches Nothing

THE AIM for today’s entry is to resume our review of Peter Scholtes’ six new leadership competencies by taking a look at the third entry, Understanding How We Learn, Develop, and Improve; Leading True Learning and Improvement.

The Learning Imperative

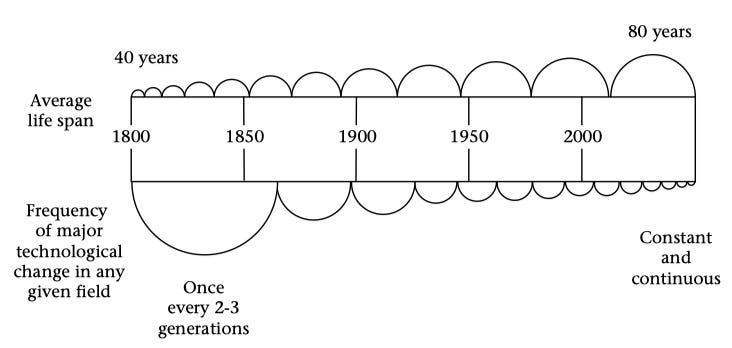

Why is learning so important for new leaders to understand and internalize as a core competency? As shown in the figure below, Scholtes identifies two interrelated reasons: our increasing lifespans and the commensurate increasing frequency of major technological leaps:

Consequently, it isn’t a cliché to say the pace of change is getting faster, however our ability to adapt and learn is definitely being pressed. For many organizations learning is the constraint: those who learn quicker will succeed over those who do not.

To overcome this, Scholtes’ remedy, much like that of Dr. Deming, is to recognize life-long learning is an imperative that schools need to nurture and lead by teaching students how to learn rather than what. Commensurate to this is a radical rethinking of what it means to provide on-the-job learning and how to design systems and policies to support this.

Dr. Deming was an example of an inveterate life-long learner, famous for collecting tidbits of information on scraps of paper that would make their way into his thinking and writing that could lead to profound changes in prior positions which he would vociferously defend by stating “I make no apologies for learning!”.

Theory, Hypothesis, Hunch, Guess

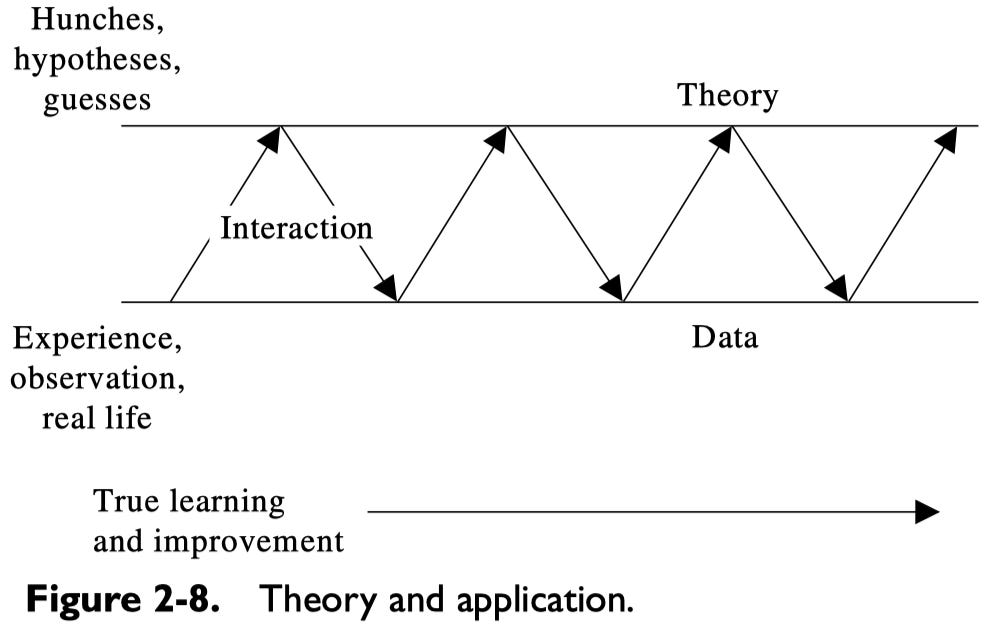

In Out of the Crisis and The New Economics, Dr. Deming keenly observes that without theory, experience teaches nothing—all we need is a hunch or guess on what we predict will happen to begin accumulating knowledge about what to do to improve. Knowledge is the product of the dynamic interplay between a theory and experiential feedbacks, which Scholtes illustrates below, borrowing from a similar illustration by Prof. George Box:

This can seem really obvious and self-evident, but its implications aren’t well considered when we step outside of the classroom or lab and into an organization. How often do we see firmly-stated dictums standing in for a testable hypothesis? For example:

The best sales reps need bonuses to reach top-performance

Annual appraisals are how we reward top employees and get rid of laggards

Layoffs are a necessary part of the modern business cycle

Across-the-board cuts are the fairest way to find savings

Good management depends on finding the “single, wringable neck”

Pushing new practices on to teams will help them become more productive

Deming pressed on this point hard with his students and clients, asking them how they know what they know if they have no data or documentation to back it up. He would often deflate the grandiose visions of executives with two simple questions: “How? By what method?”

So, if our aim is to test our theories, hypotheses, hunches, or guesses so we can build knowledge, what method would we use?

Systematic Learning: PDSA

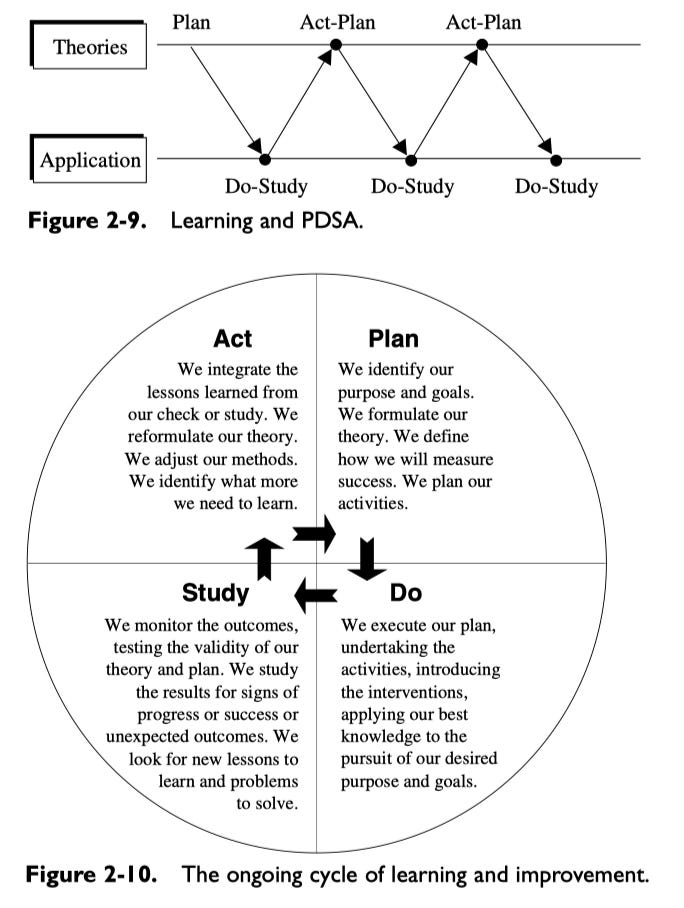

Scholtes, taking guidance from Deming, advises leaders to develop the skill of structuring their learning into Shewhart Cycles, aka PDSA loops, so as to systematize learning. We first looked at these in my Nov. 12/21 newsletter which you can check out for more details.

It looks like the following:

PDSAs can be broadly applied to organizational improvements and activities at any scale or time frame, eg. long-range annual planning, quarterly reviews, or even weekly staff meetings. Wherever there is a recurring process or cycle that we want to monitor and improve, a PDSA will help. The only caveat is to not try to do too much at once, or so little that nothing of use is learned — this is a skill that takes time to get right, as we are often overly-optimistic in our assessments of our targets for change and how to change them.

NB: Bear in mind that a single PDSA can reveal our initial theory was wrong, a strong signal that we have learned something valuable that often goes disguised as a failure mode. It’s up to us to decide what to do with this knowledge. In The New Economics, Dr. Deming advises that “No number of examples establishes a theory, yet a single unexplained failure of a theory requires modification or even abandonment of the theory.”

Learning Styles: Visual, Auditory, Kinesthetic

In addition to understanding how we generate and accumulate knowledge, leaders also need some appreciation for theory behind the patterns learning styles we all have. Scholtes suggests exploring the research of Dawna Markova that she wrote about in her 1996 book, The Open Mind.

According to Markova, contrary to a commonly-held belief, we’re not one-dimensional learners, eg. “I’m a visual learner” or “I learn by doing”. Instead, our learning is spread across three perceptual “channels”: Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic (experiential) that work together to inform our learning processes, triggering brain wave patterns that produce six different types of cognition:

AKV, AVK

VKA, VAK

KAV, KVA

The first “channel” in the pattern is the one we feel most comfortable with using to process novel information, while the second and third channels are what makes the learning “stick”. This insight can have profound implications for how we design training to communicate complex tasks or new methods for managing our work.

For example, it is stock-in-trade for agile coaches to have an assortment of hands-on activities to teach software development teams about how to approach working in an agile way, including fun and engaging games and simulations. They are all predicated on the (somewhat untested) theory that people learn these concepts best through experience (K), followed by a debrief (A), with learnings that are aggregated and displayed for everyone to see (V). However, given Markova’s theory, we could be losing people who learn differently, especially when it comes to extrapolating concepts from an abstract game and applying them in-situ, suggesting that we might want to run some PDSAs to evaluate the effectiveness of the exercises and modes of delivery.

Another adjacent example: My son’s high-school has classrooms that are predominantly laid out in rows of desks facing a set of white boards where the teacher delivers lessons in a lecture format. What type of learning patterns does this layout encourage or discourage? How could the classroom be designed to promote different styles of learning?

What Not to Do

In brief, Scholtes advises leaders to escape a self-laid trap that emerges when they disregard or try to “average-out” an understanding of the theory behind how people learn, develop, and improve. Without this knowledge, you are more prone to errors in judgment and action and likely to over or under-react to various day-to-day phenomena in the organization.

For example, you might confuse an off-the-cuff change as an improvement, subsequently becoming in thrall to an overly-optimistic illusion rather than a real improvement. Or you might see problems emerge and disappear, remaining elusive and unsolved because no knowledge or insight was gained from prior reactions. Worse still, you could become captured by the latest trends and fads, creating cynicism among employees as they are exhorted to adopt this or that practice without rhyme or reason.

Summary

Scholtes’ third new leadership competency urges us to gain an understanding of how people learn, develop, and improve as an imperative to meet the accelerating pace of change, which hasn’t slackened since the publication of The Leader’s Handbook in 1998. At the fundamental level, this means a systematic approach to building knowledge by testing our theories, hypotheses, hunches, and guesses with PDSAs. Complementary to this, we also need an appreciation for how others learn new and novel concepts and methods, which we can glean from researchers like Dawna Markova and her theory of the three channels of cognition, among others, to help inform the design of training and how it is best delivered.

By developing this competency, leaders are best-positioned for taking on, and sharing, the work for improving the quality of their operations by allowing learning to take priority.

In our next instalment, we’ll review Scholtes fourth new leadership competency, which is closely related to the third: Understanding People and Why They Behave as They Do.

Reflection Questions

Consider what we’ve learned from reviewing Peter Scholtes’ third new leadership competency in your own context:

How is well-integrated is learning in your organization?

How are interventions into various systems and processes regulated? Are they made on a best-guess basis, or through rigorous testing of hypotheses? Or somewhere in between?

How has learning been designed into the culture?

How is failure tolerated? How is success recognized?

How are learnings shared across the organization, between teams and departments?

What types of policies are in place to encourage learning?

Consider the example of my son’s high school classrooms and the kinds of learning styles they have been designed to support: What styles of learning has your organization been designed for? Consider this carefully if you are remotely distributed.

Suggested Reading

HBR: How One Fast-Food Chain Keeps Its Turnover Rates Absurdly Low (Jan 26/16)

The story about how Pal’s Sudden Service builds continual learning into their leadership by requiring them to spend 10% of their time teaching new concepts or ideas to peers and employees.

Moen, Norman, and Colleagues: The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance.

The OG guide for learning how to improve through the application of PDSA cycles. Within you will learn the three questions that should precede any improvement: What are we trying to accomplish? How will we know a change is an improvement? What changes can we make that will result in an improvement?

Spear, Steven J. The High Velocity Edge.

An engaging read about the core competencies that high-performing organizations across a wide swathe of industries and eras have used to put themselves in a class apart from their competition. Pay particular attention to Capability #3: Knowledge Sharing.