Are You In Favour of Layoffs?

It's All But Inevitable Under the Prevailing Style of Management

It is no longer socially acceptable to dump employees on to the heap of unemployed. Loss of market, and resulting unemployment are not foreordained. They are not inevitable. They are man-made.

Deming, Dr. W.E. Out of the Crisis. (p. ix)

The day is here when anyone deprived of a raise in pay or of a job because of low rank may with justice file a grievance. He will win his case.

In the United States, the last ones to suffer are the people at the top. Dividends must not suffer.

In Japan, the pecking order is the opposite. A company in Japan that runs into economic hardship takes these steps:

Cut the dividend. Maybe cut it out.

Reduce salaries and bonuses of top management.

Further reduction for top management.

Last of all, the rank and file are asked to help out. People that do not need to work may take a furlough. People that can take early retirement may do so, now.

Finally, if necessary, a cut in pay for those that stay, but no one loses a job.

Deming, Dr. W.E. The New Economics, 3rd ed. (p. 20)

It is a mistake to suppose that efficient production of product and service can with certainty keep an organization solvent and ahead of competition. It is possible and in fact fairly easy for an organization to go downhill and out of business by making the wrong product or offering the wrong type of service, even though everyone in the organization performs with devotion, employing statistical methods and every other aid to boost efficiency.

Your customers, your suppliers, your employees need your statement of constancy of purpose — your intention to stay in business by providing product and service that will help man to live better and which will have a market.

Deming, Dr. W.E., Out of the Crisis. (p. 25)

THE AIM for today’s post is to consider the practice of layoffs for stabilizing a business through the lens of Dr. Deming’s teachings and whether they are an inevitable (and predictable) consequence of the prevailing style of management. This past month alone we’ve seen tremendous job losses in the tech and tech-adjacent sectors, totalling over 90k by some estimates, with the predominant reasons given by leadership that the moves were necessary to improve efficiency and profitability for the future survival of the business.

Some Examples from the Field

Streaming music giant, Spotify, announced on January 23 a reduction of 6% of their workforce because of “a need to become more efficient”, owing to the leadership team misjudging the post-pandemic market and demand for their service to go ever up-and-to-the right. CEO Daniel Ek admitted to allowing OPEX to grow twice as fast as revenue.

Venerable software Goliath, Microsoft, announced on January 18 a reduction of 5% of their head count (10,000 souls world-wide), to “align [their] cost structure with revenue” and “invest in strategic areas for our future”. CEO Satya Nadella offered a clarion call to those who survived to “raise the bar and perform better than the competition to deliver meaningful innovation… If we deliver on this, we will emerge stronger and thrive long into the future; it’s as simple as that.”

Big Blue icon, IBM, announced on January 26 they were culling 3,900 jobs world-wide (1.5% of total workforce), due to “the company’s failure to achieve its annual cash target”. The effort is seen to put the firm in-line with their US peers who are “reducing their workforce and cutting down expenses to better adjust to the global economic downturn.”

Online retailing phenom, Amazon, announced on January 4 a plan to eliminate “just over 18,000 roles” mostly targeted in Amazon Stores and PXT organizations. CEO Andy Jassy states in a blog post that “these changes will help us pursue our long-term opportunities with a stronger cost structure”, and that he’s “optimistic that we’ll be inventive, resourceful, and scrappy in this time when we’re not hiring expansively and eliminating some roles.” Further, “Companies that last a long time go through different phases. They’re not in heavy people expansion mode every year.”

Software and hardware giant, Google, announced on January 20 the immediate culling of 12,000 jobs (6% of total workforce). CEO Sundar Pichai admitted in a memo to staff explaining the cuts that over the past two years “we hired for a different economic reality than the one we face today.” Pichai also said he was “deeply sorry” and that the changes “weighs heavily on me, and I take full responsibility for the decisions that led us here.”

Observe the themes in these announcements and others: the leadership are mere victims of economic circumstance, putting forth their best efforts; the decisions weren’t taken lightly, and it was difficult to make them; the market conditions changed; our costs overran our revenue; we grew in a different economic reality than the present.

It’s all unfortunate, but an inevitable consequence of top-management’s decisions guided, perhaps unwittingly, by the theory of management they hold.

Are Layoffs Inevitable?

In his seminars, Dr. Deming would pose a thought experiment in the form of a referendum question on whether people were in favour of quality (prediction: landslide in the affirmative) and would subsequently ask how that was to be achieved.

We can re-purpose this question and similarly ask: Are you in favour of layoffs? (prediction: landslide in the negative). We could then ask a follow-up: “Then why do you inevitably manage your way towards them?” Pause and consider this for yourself.

Layoffs occur when management, to borrow a phrase from Dr. Deming, “knows not what to do” when conditions become unfavourable because they did not know how or what to manage when times were good. Consequences from decisions accrue and top-management feels left with little recourse but to reduce visible costs, including staffing. However, as I cover in my September 17/21 newsletter on Management by Objective, this comes with invisible costs to the organization that may not be apparent until well after the event. In some circumstances, the layoffs may precipitate more cutbacks and layoffs until the business can no longer be sustained.

NB: This doesn’t mean that leadership can’t benefit from a lucky series of events in their favour - see my August 16/21 newsletter, Taking Only the Top Percent. Unfortunately, this will delay the needed epiphany to reexamine core beliefs and theories that can give the nudge to seek better ways.

Some of the ways that leadership are led to layoffs include the following, which we’ve covered in previous newsletters:

Ultimately, layoffs are a violation of the first of Deming’s 14 Points, as expressed in his first and second Deadly Diseases:

Lack of constancy of purpose to plan product and service that will have a market and keep the company in business, and provide jobs.

Emphasis on short-term profits: short-term thinking (just the opposite of constancy of purpose to stay in business), fed by fear of friendly takeover, and by push from bankers and owners for dividends.

When Layoffs and Performance Appraisals Collide

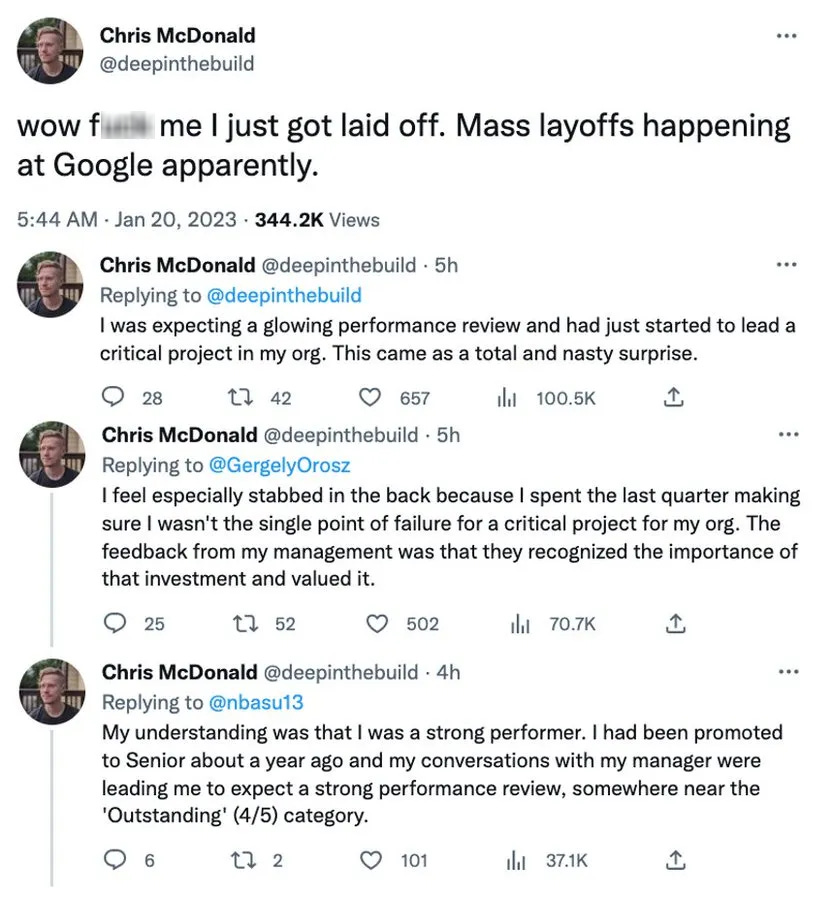

Nowhere is the incoherence and tyranny of the prevailing style of management made more apparent than in situations where employees discover that years of hard work and dedication, glowing reviews, and promotions do nothing to spare them from the axe or the disorienting realization that in the end, it was never really about their performance, it was all a matter of luck and rewarding the weatherman for a nice day:

Deming would have harsh words for senior management that indulges in this cretinous behaviour for it utterly destroys any semblance of teamwork afterward. Who would be foolish enough to trust the word of leadership that “we’re all in this together” again?

What to Do, Instead?

Deming was loathe to give prescriptive answers or examples as solutions to problems because this tended to “switch off” recipients’ brains and lead them to copying without understanding the theory behind the remedies. This said, he observed that in Japanese companies (of the time) the order of operations was inverted to what was practiced in America: Those at the top are the first to suffer:

Cut the dividend. Maybe cut it out.

Reduce salaries and bonuses of top management.

Further reduction for top management.

Last of all, the rank and file are asked to help out. People that do not need to work may take a furlough. People that can take early retirement may do so, now.

Finally, if necessary, a cut in pay for those that stay, but no one loses a job.

I was surprised to find ONE American company which has demonstrated at least a fraction of this guidance: Apple:

While a step in the right direction, there are a few things to note:

Cook didn’t reduce his bonuses of his own volition, but on recommendation of the Board’s Compensation Committee after getting some flak from shareholders, as described in Apple’s 2023 SEC filings:

In the same filing, Cook is listed as the only senior leadership team member to have their compensation reduced.

Apple is most definitely not a Deming-led organization: They are very much an old-school, pay-for-performance/merit-pay shop who strongly believes in bribing the best performance out of their executives. The SLT is biased and measured across multiple targets to get their awards.

So, Why Hasn’t Apple Laid Anyone Off?

As noted, Apple is nowhere near thinking in-line with a Deming-led mindset nor are they emulating a Japanese firm that starts at the top and works their way down before laying people off. This said, they are showing some signs of enlightened management by being more cautious in hiring (so as to avoid wild understaff/overstaff oscillations as described by Rule #3 of the Funnel Experiment) and preferring to rely on attrition to naturally reduce staffing levels:

Managing Toward Layoffs

Are layoffs inevitable? When we choose to focus on visible figures and phenomena, we begin to close off our thinking to alternative theory and practice that could make them a truly rare occurrence. By not having an overarching constancy of purpose toward job creation through pursuit of improvement of quality throughout the organization, people become reduced to costs with no ancillary benefit - one person is as good as another. With this reductionist, parts-in-isolation view, leadership will always feel helpless and tempest-tossed, unaware that as they quell one cycle, they inadvertently set the stage for the next.

Reflection Questions

Consider the excerpts and examples above in relation to your own experiences and observations. How has leadership responded to times of economic or market-driven hardship? Were layoffs inevitable an inevitable consequence? Why? Did top-management take the hit first? Last? At all? What was the effect on those who “survived” ? What was gained? What was lost?

Did management conduct performance appraisals, then lay off the appraised indiscriminately? Were remaining staff cynically urged, without any further help or direction, to “raise the bar” to “boost performance” and best the competition? How was this received? What happened next?

What do you think is the primary obstacle to adopting an order of operations similar to the one Japanese firms use that Deming describes? Do you have an example of a firm that practices a similar way of avoiding layoffs?