Taking Only the Top Percent

Confusing Luck for Exceptionalism

"Keep the place open to the best workers. Fantastic contribution to management! Some companies take the top percent of the class. Serves them right."

- Dr. W.E. Deming, commenting on motivation for Day 4 double-shifts with above-average workers of the Red Bead Experiment

In my experience, most troubles and most possibilities for improvement add up to proportions something like this:

94% belong to the system (responsibility of management)

6% are attributable to special causesWe shall understand these proportions after we do the experiment on the Red Beads (Ch. 7).

No amount of care or skill in workmanship can overcome the fundamental faults of the system.

- Dr. W.E. Deming. The New Economics, 3rd ed. (p. 24)

As to the influence and genius of great generals—there is a story that Enrico Fermi once asked Gen. Leslie Groves how many generals might be called “great.” Groves said about three out of every 100. Fermi asked how a general qualified for the adjective, and Groves replied that any general who had won five major battles in a row might safely be called great. This was in the middle of World War II. Well, then, said Fermi, considering that the opposing forces in most theaters of operation are roughly equal, the odds are one of two that a general will win a battle, one of four that he will win two battles in a row, one of eight for three, one of sixteen for four, one of thirty-two for five. “So you are right, General, about three out of every 100. Mathematical probability, not genius.” (John Keegan, The Face of Battle, Viking, 1977.)

- As quoted by Dr. W.E. Deming. Out of the Crisis (MIT Press) (p. 394).

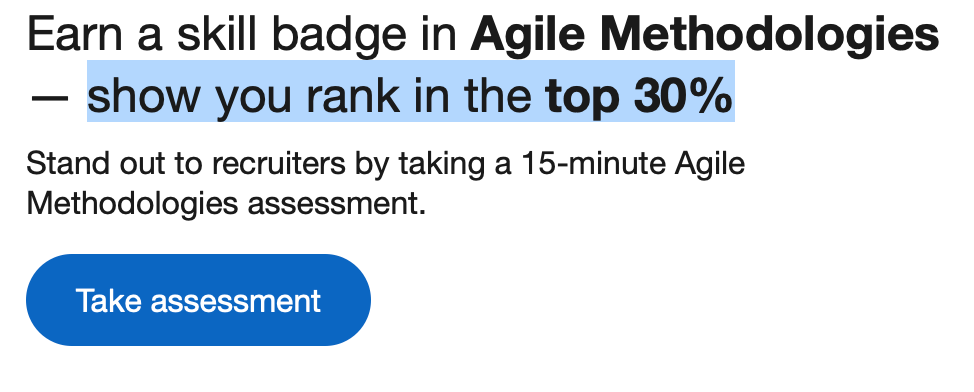

RECENTLY, I received the following item from LinkedIn that shows just how durable and relatable Dr. Deming’s teachings are some twenty seven years after his passing. What observations or questions does it raise for you? What embedded assumptions are presented here?

At first glance, I was reminded of the old expression used with horseshoes and hand-grenades: “It’s not luck, it’s skill…” Here’s what else I see:

An arbitrary ranking within an arbitrary system, that being a LinkedIn pool that gets farmed out to an ecosystem of an unknown number of recruiters, each of varying quality and competency;

Ranking is ambiguously-defined: Rank according to absolute score or population?

Arbitrary specification thinking, eg. “in-spec” is top 30%, out of spec bottom 70%;

The “top 30%” will always be a random pool according to variation; someone will always be pushed outside the limits as more and more are added;

A false proxy for assessing competency and quality.

Random Results of Systemic Variation

Dr. Deming was consistent throughout his system of thinking on why ratings and rankings should not be used as a proxy for determining quality of people: Because the rankings belong to the system that created them (and thus management), and not the appraised candidates. Change the questions, change the results, change the rankings. Candidates will rise and fall accordingly.

In a 2009 HBR article, Are “Great” Companies Just Lucky? (spoiler alert: yes) the authors make a very Deming-aligned observation that many success studies (a form of rating and ranking) are “simply imposing patterns on random data”, and conclude: “That’s not science, that’s astrology.” By way of example, they relate an exercise that Prof. Rebecca Henderson of MIT’s Sloan School of Business conducts with students:

“I begin my course in strategic management by asking all the students in the room to stand up,” she says. “I then ask each of them to toss a coin. If the toss comes up tails, they are to sit down, but if it comes up heads, they are to remain standing. Since there are around 70 students in the class, after six or seven rounds there is only one student left standing. With the appropriate theatrics, I approach the student and say, ‘How did you do that? Seven heads in a row! Can I interview you in Fortune? Is it the T-shirt? Is it the flick of the wrist? Can I write a case study about you?’” Henderson’s charade reveals the folly of attributing outcomes arising from systemic variation (the random nature of coin tosses) to the supposedly unique attributes of a few individuals, who are really just the luckiest coin flippers. Similarly, we can credibly claim that a firm is remarkable only when its performance is so unlikely that systemic variation alone cannot account for its results. Most success studies don’t address this fact, relying instead on the “self- evident” nature of exceptional performance.

Note how the criteria the authors use for assessing a credible claim for exceptional performance is effectively the difference between a special-cause or common-cause of variation, to use Dr. Deming’s definitions. Were we to plot the the metric used in assessing company performance on a process behaviour chart, we’d see hints of exceptionalism in the data points that go beyond the upper process limits - the rest would be random noise.

Reflection Questions

Let’s connect everything together in consideration of Dr. Deming’s above-noted thoughts and observations and what you are seeing in your own organization. What instances can you think of where you or your leadership has made a decision based on an assumption of exceptionalism based on an arbitrary rating or ranking? What thresholds were chosen? What informed them? What were the consequences of the decision? If the predictions proved correct, what was attributed: Skill or luck?

Try out Prof. Henderson’s exercise with your colleagues. Count the number of coin flips and plot on a process behaviour chart. Did the winner of the contest present truly exceptional performance, or just the luck of the draw? How many sources of variation can you and your colleagues identify? NB: The theory of variation used in a process behaviour chart states that data points outside of the upper limits (a 3-sigma estimate above the mean) are exceptional and worth investigating. How many data points did you find that fit this criteria?

Extra Credit Reading

The above-mentioned HBR article served as a foreword to a really interesting 2012 Deloitte study, A Random Search for Excellence that should be mandatory reading for any leadership team undertaking a transformation that is based on naive emulation of other “great” companies. I think it could be augmented further with a Deming perspective on the difference between enumerative and analytical studies.