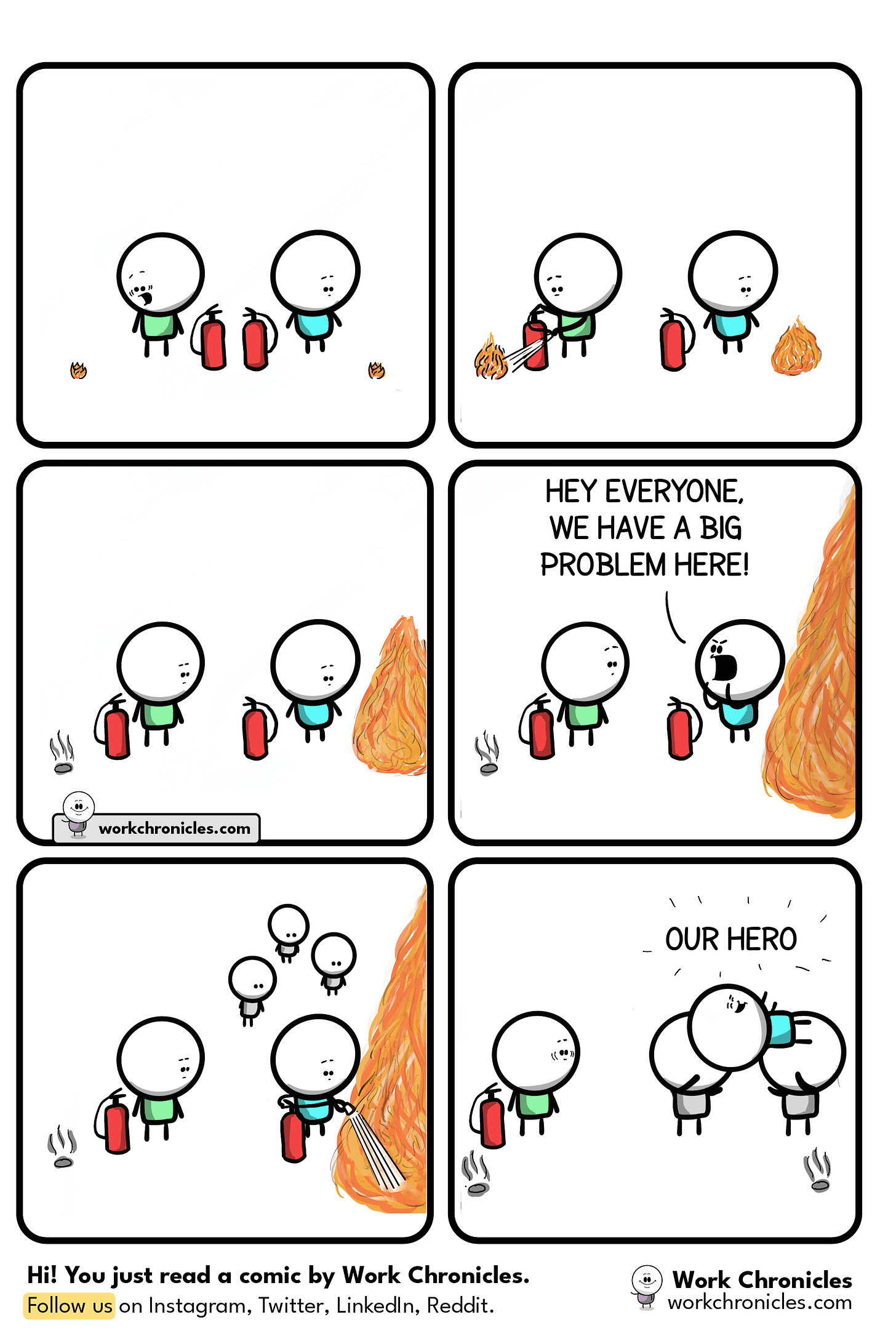

Heard in a seminar. One gets a good rating for fighting a fire. The result is visible; can be quantified. If you do it right the first time, you are invisible. You satisfied the requirements. That is your job. Mess it up, and correct it later, you become a hero.

Deming, W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis (MIT Press) (p. 107). The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

Putting out fires is not improvement of the process. Neither is discovery and removal of a special cause detected by a point out of control. This only puts the process back to where it should have been in the first place (an insight of Dr. Joseph M. Juran, years ago)…

Adjustment of a process that is in statistical control, initiated on appearance of a faulty item or a mistake, as if it arose from an obvious immediate cause, will only create more trouble, not less (a theorem due to Lloyd S. Nelson; see p. 20; also p. 110). Specification limits are not action limits (see Ch. 11).

Deming, W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis (MIT Press) (p. 51). The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

You are in a hotel. You hear someone yell fire. He runs for the fire extinguisher and pulls the alarm to call the fire department. We all get out. Extinguishing the fire does not improve the hotel.

That is not improvement of quality. That is putting out fires.

Deming, W. Edwards. Seminar, Feb 5-8, 1985. As quoted in: Walton, Mary. The Deming Management Method (Perigee Business) (p. 67).

THE AIM of today’s post is to review the management malpractice of firefighting: the reactive, short-term method for treating every deviation from an expected “norm” as a crisis and acting quickly to snuff it out using whatever is at hand to restore operations back to their prior normal state. It can be thought of as the preference to manage symptoms over systems.

Perfectly Designed Instability

In my January 19th newsletter, I recalled Dr. Deming’s reproach of how “Stamping out fires is a lot of fun, but it is only putting things back the way they were.” Fighting fires in this way is borne of the belief that when things go wrong, they do so because of some circumstance rather than presenting a possible signal of built-in instability. Putting out fires helps to restore the system to its prior state, which is presumed to be “perfect” or “desirable” despite its inherent systemic defects which can, ironically, produce more fires to fight. Cynically, this presents opportunities for organizational arsonists who take advantage of this phenomena to play the hero.

Thus, by extension, the system (including its remedial processes) is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.

Fixes that Fail

No discussion of firefighting is complete without referencing the systems archetype of “Fixes that Fail”, a common pattern of cause and effect that originates in the systems dynamics field that Jay Forrester was notable for promoting. I first presented this in my July 15, 2021 newsletter on Management by Results - see that discussion for reference, but in brief it describes how reactions to symptoms through implementation of naive fixes contributes to the creation of unintended consequences that take time to appear.

In the case of firefighting, it is the act of firefighting itself that sets in motion the various phenomena that will sooner or later bring about another round of firefighting.

Rx: Improve the System

In contrast to this common practise, Point 5 of Dr. Deming’s 14 Points for Management calls our attention to focus on improving the system, constantly and forever. I quite like how Dr. Henry Neave frames this in The Deming Dimension:

Improve constantly and forever the system of planning, production, and service, in order to improve every process and activity in the company, to improve quality and productivity, and thus to constantly decrease costs. It is management’s job to work continually on the system (design, incoming supplies, maintenance, improvement of equipment, supervision, training, retraining, etc…

This [mindset] is the basic difference between intelligent management and crisis management.

Neave, Dr. Henry. The Deming Dimension (SPC Press). (p. 42)

In order to improve the system, you need to understand how it works, and that requires mapping to see what inputs and outputs are contributing to causing the fires. In turn, this means leaving nothing outside of the investigation: Quite frequently, the cause will be found well-upstream of the incident and residing in a core management practise.

Breaking the Cycle

A corollary to Point 5 with respect to firefighting is to cease rewarding the practise of smothering fires and doing late-stage post-mortems that tend to address local optimizations in favour of an integrated practise of whole system improvements. Better yet, embrace the philosophy that I learned from friend and mentor Dr. Bill Bellows, to fix problems before they appear according to the old adage of “a stitch in time saves nine”.

Reflection Questions

Consider the above-quoted passages by Dr. Deming in the context of your own organization or experience. How are fires remediated? Who or what behaviour is rewarded? What is punished? What have been the long-term consequences? Are deeper, systemic improvements pursued? How are changes implemented to “fix” the problems? What are the impacts to customers for repeated cycles of firefighting? Does anyone know or care? How could you begin to change the philosophy of firefighting in your immediate sphere of influence?

Bonus Question: Is the cost of fire fighting incorporated into your product’s or service’s margin and markup?