Management by Results

More Trouble, Not Less.

Present Practice: M.B.R. (management by results): Take immediate action on any fault, defect, complaint, delay, accident breakdown. Action on the last data-point.

Better Practice: Understand and improve the processes that produced the fault, defect, etc. Understand the distinction between common causes of variation and special causes, thus to understand the kind of action to take (Out of the Crisis, pp. 309).

The outcome of management by results is more trouble, not less.

What is wrong? Certainly we need good results, by management by results is not the way to get good results. It is action on an outcome, as if the outcome came from special causes. It is important to work on the causes of results - i.e., on the system. Costs are not causes: costs come from causes (Gipsie Ranney, 1988).

- W.E. Deming, The New Economics, 3rd Ed., p. 24.

What are the implications of managing an organization’s system by its results? For Dr. Deming, it's more troubles, not less because we overreact to normal fluctuations in common-cause variation of outcomes as if they were true causes for alarm, causing even more problems in the process. Without any theory or knowledge about these effects, how could we know otherwise?

In Peter Senge's 1990 book, The Fifth Discipline, he describes a nightmare scenario of Management by Results called compensating feedback - and it's more prevalent than you might think:

[W]hen well-intentioned interventions call forth responses from the system that offset the benefits of the intervention. We all know what it feels like to be facing compensating feedback—the harder you push, the harder the system pushes back; the more effort you expend trying to improve matters, the more effort seems to be required.

It doesn’t require much imagination to think of examples where this has occurred, especially in the past year! Anywhere where figures are compared that provoke a commensurate reaction in leadership, you will find the MBR phenomena of compensating feedback.

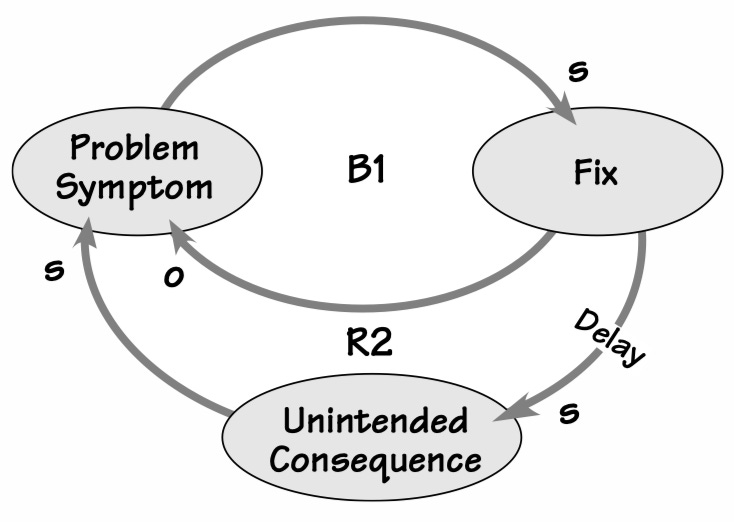

In the discipline of systems dynamics, this is described by the Fixes That Fail system archetype: a "problem" that cries out for a solution which produces a host of unintended consequences that worsen the problem over time, causing demand for more fixes that fail. Using causal loop diagram notation, it looks like this:

How to Read: Begin with the Fix node; as fixes are introduced (increases), the Problem Symptom decreases (O means “moves in the opposite direction”) while after a period of time, the Unintended Consequence increases (S means “moves in the same direction”). As Unintended Consequences increase, the Problem Symptom also increases. As the Problem Symptoms increase, so do the Fixes.

Contrary to the impulses we might have, in most cases (ie. the literal house isn’t burning down) it may be better to do nothing at all and just observe what the system is doing before choosing when and how to intervene.

Instead, ask: How do we know what’s caused the particular fault or fluctuation? How has the system performed previously over time? Why do we think our reactions will lead to improvement? By what method will we make changes? How will we know if we’re right?

As for the unseen William Tell in our cartoon, what sources of variation can you think of that are leading his arrows astray? What could he do to better-hit the apple off his assistant’s head?