New Competency #4: Understanding People and Why They Behave as They Do

Why We Get From Others What We Expect

THE AIM for this newsletter is to review Peter Scholtes’ fourth of six new leadership competencies, Understanding People and Why They Behave as They Do, from his 1998 book, The Leader’s Handbook. What follows shallow dive into the domain of the psychology of human interactions and activity, which Dr. Deming deemed to vital for management to learn that it comprises one of the four domains of his capstone theory, The System of Profound Knowledge.

Below, we’ll learn a little about what makes people tick, their motivations, and how trustworthy relationships are built or destroyed.

For those catching up, I recommend reading over Competency #1, #2, and #3 in our prior newsletters.

Why People Do What They Do

Scholtes bluntly asserts that there is a significant mismatch between the humanitarian rhetoric of management (“people are our most important asset”) and the reality of leadership predispositions and actions.

Drawing upon the work of Douglas MacGregor (he of the Theory X/Y model) Scholtes explains that first and foremost we get the behaviour from people that we expect: Either they want to avoid work and need strong direction (Theory-X), or they are self-starting, eager to learn, and seek out opportunities to take on greater responsibilities (Theory-Y). Theory-X managers see the world through the lens of incentives and coercion with carrots and sticks, while Theory-Y managers see beyond this simplistic world-view, realizing that the employee will support organizational goals if they help to further their own sense of worth and development. Theory-X managers in particular tend to be predisposed to what Deming referred to as the Pygmalion Effect (see Mar. 28/22 newsletter) where we view an individual’s past as prologue: once a winner or loser, always a winner or loser.

Put more succinctly, people behave rationally to the system they work within. This leads us naturally to the topic of how do we motivate employees?

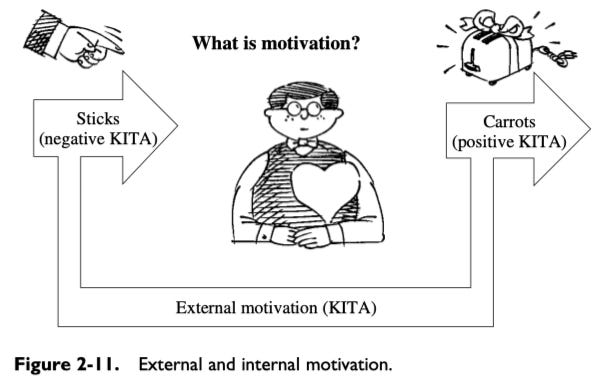

Motivation by KITA

Scholtes references a classic 1968 HBR paper by Frederick Herzberg that asks, “One more time: How Do You Motivate Employees?”. Spoiler alert: You don’t, however, there are almost infinite ways under the prevailing modes of management to demotivate them. In the paper, Herzberg describes the prevailing Theory-X thinking that people are best-motivated by [swift] Kicks-in-the-Ass, which come in two thoughtful varieties: Negative (sticks) and Positive (carrots). Absent from this calculus is any consideration to what motivates a person intrinsically:

Both KITAs come with two attendant problems: First, they only work in the short-term to ensure simple conformity to a standard or request; second, they have a negative impact on the relationship between the motivator and the motivated and their co-workers. With respect to carrots, Scholtes makes a biting observation that they can also be considered a form of unacknowledged bribery:

Consider the implications of someone being able to motivate you to a higher level of performance through some kind of reward. What this would say about you is that you have been withholding some reservoir of effort, waiting for it to be bribed out of you. None of us would say that about ourselves. Nor do we say others are holding back, waiting for a bribe. However, with our contests and merit pay and incentive bonuses, we act as though it were true. (p. 38)

He goes one to explain that when we indulge in this form of managing people we automatically gain a dysfunctional parent/child relationship for the bargain and, just like a family, foster internal competition for rewards among the “kids”. In this atmosphere of winners and losers teamwork and cooperation is the exception to the rule and degrades as appraisal time approaches, and for the losers, weeks to months afterward.

What Happens When You Take Incentives Away?

Dr. Deming observed that incentives like bonuses and “merit pay” work, it’s only at what cost to the system that’s up for debate. But what happens if, after creating a dependency on them, you take them away? Short answer: nothing good.

Scholtes tells the story of an old incentive program restaurant chain Pizza Hut sponsored in the 90s to encourage students to read by offering free pizzas for every ten books they read. Kids being kids, they looked to get the reward with the least effort and began to read shorter and shorter books. All was well until the program came to an eventual end and parents and teachers discovered that without the pizzas the kids read less, if at all, and what they did read was shorter and less challenging. If the mission was to dissuade reading, mission accomplished.

In my April 23/23 newsletter, Mini-Case Study: The Case of the Lost Bonuses, I share a similar story about a CEO who, facing a $26M revenue shortfall, scolded her employees (the “kids”) during an internal townhall for asking about whether their bonuses were safe. She tersely explained their job was to find the revenue, regardless.

Her rude tirade unintentionally revealed the unspoken truth about incentive programs: they were never really about driving individual performance in the first place. If they were, you’d think no expense would be spared when the chips were down.

The “I’m Ok, You’re NOT Ok” Anti-Pattern

Scholtes argues there is yet another problem with the dominant parent/child relationship anti-pattern in that it tacitly sends the message from the parent/manager to the employee/child: “I’m OK, you’re NOT!”. He expands this into one of four possible stances in the diagram below, with “OK” as equivalent to being competent, reliable, trustworthy, and having high-value as a person and employee, and “Not OK” meaning the exact opposite:

Only one of the stances, “I’m OK, you’re OK”, represents a healthy relationship, with the other three being different forms of what he calls a “social pathology” (Deming might have called them “diseases”) that characterizes the typical guarded and impersonal boss/subordinate relationship:

I’m OK: YOU need motivation, carrots and sticks, annual appraisals.

I’m doing my best, YOU need to be bribed with incentives to do the same.

This behaviour is hard-coded into the prevailing style of management, the prison that Deming describes in The New Economics that regulates our interactions: managers aren’t supposed to take an interest in forming a human relationship with subordinates because they need to be stern task-masters.

By way of contrast, Scholtes describes the management style of Tom Chappel, owner of Tom’s of Maine, a natural hygiene products company that still exists today. Chappell encouraged the forging of personal relationships with and among staff so as to know each other well beyond their job descriptions and categories. His view was of his business as a system of human relationships that extended to suppliers, owners, financial partners, the community, local government and beyond.

Personally, I’ve only worked with a handful of managers who have taken a genuine interest in building relationships with their people, and much like a business who treats their customers well, have a loyal following that cannot be bought. People want to work with them because a mutual trust has been built between them.

But, what is trust?

Trust, Respect, Affection

For Scholtes, trust is at the nexus of two converging beliefs between people: benevolence and aptitude. When each party in the relationship believes the other is competent and cares about them, we have mutual trust:

While we may begin a relationship with high benevolence or aptitude, these alone won’t get us to trust one another, although it will be easer than working from a place of distrust. This takes time and effort to demonstrate; if there is any doubt, the relationship will slide backward.

In his classic business fable, The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Patrick Lencioni describes Dysfunction #1 as Absence of Trust, the unwillingness to be vulnerable and open within the group. Without trust, teams cannot progress to higher functional states because they’re devoting time to defensive postures and politics. This condition is illustrated by the Distrust quadrant. Moving to trust and beyond is the thesis of Lencioni’s book, however, Scholtes suggests it can begin by taking on simple, low-risk activities together such as learning something new, and then gradually ramping up the challenge as trust is gained, thereby moving the needle along the benevolence and aptitude axes simultaneously.

In my line of work we call this “quick wins” - the low-hanging fruit that can pay outsized dividends for the effort and get us to higher and more challenging plateaus by demonstrating competence and effective cooperation. For example, to build trust for implementing a lean based approach to software delivery, we might choose a small optimization project and work in tight, 1 week cycles to show regular progress and how to communicate about impediments and dependencies. We’ll then couple this with the “Stone Soup” method of incrementally engaging others for improvements to expand trust, eg. “You know what would improve this flow? If we could meet more frequently to clear out impediments…”

Summary

In this entry we’ve taken a brief look at Scholtes fourth new leadership competency concerning understanding people and their behaviours. Principally, we’ve learned that people act rational to the system they work within, constructed by the predominant beliefs and expectations of management. In turn, these shape attitudes on motivation by using blunt instruments like incentives and penalties to coerce behaviours, which when they falter will lead to the default state of management: distrust. Getting beyond this state requires a much deeper appreciation and understanding of the psychology of people and teams in organizations and is the table-stakes for leadership who wish to lead with a systems view.

In our next instalment, we’ll look at Scholtes’ fifth new leadership competency, Understanding the Interaction and Interdependence between Systems, Variability, Learning, and Human Behaviour, and Knowing How Each Affects the Others.

Reflection Questions

Consider your own organization and experiences through the lens of Scholtes’ fourth leadership competency above: Do you or your leadership subscribe to the failure modes in understanding human behaviour and the psychology of motivation and trust that he describes? How would you characterize the predominant quality of the relationship between manager and subordinate? What behaviours does this encourage?

How are KITAs used in your organization? Have you encountered situations similar to the Pizza Hut conundrum, or that of the intemperate CEO who scolded their staff about bonuses? What was the reaction and fallout? What effect did it have on morale? What do you think about Scholtes’ assertion about incentives as unacknowledged bribery?

How has leadership worked on building trust in your organization? What approaches were taken? What was the effect? Would knowledge of Scholtes’ fourth leadership competency lead to improvements? What else stands in the way?

Suggested Further Reading

Herzberg, Frederick. (HBR) One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?

This classic essay about employee de-motivation by management first appeared in Harvard Business Review in 1968 and was later re-published in 1987 and was and still is an excellent criticism of prevailing thinking on the psychology of motivation. A MUST-READ for managers.

Kohn, Alfie. Punished by Rewards.

For me, this book is the go-to for appreciating the perils of extrinsic motivation, praise, and Skinnerian behaviour modification. Deming mentions Kohn’s prior book (also a banger of a read), No Contest: The Case Against Competition, in The New Economics. Originally published in 1993 and re-released with updated reflections for the 25th anniversary issue in 2018 that provide a sober look at how we continue to undervalue intrinsic motivation.

Lencioni, Patrick. The Five Dysfunctions of a Team

A classic business fable about leadership and teamwork told in a style made popular by Eli Goldratt with The Goal. It tells the story of a tech firm whose founding CEO steps down amid rancour and discord among the SLT and the subsequent transformation initiated by the succeeding CEO who steps them through understanding the five key dysfunctions of Lencioni’s model that sabotage teamwork and how to overcome them.

While working with Dr. Deming at GM Powertrain, Mary Jenkins described three factors of motivation as Collaboration, Choice and Challenge. Later (2011) in his book “Drive” Daniel Pink gave new labels to the same three characteristics: Purpose, Autonomy and Mastery.