Einstein possessed a form of intelligence that moved beyond normal ways of formal thinking, and in doing so he often disturbed the drowsy status quo. Dr. Deming was also one of those disturbers, one of the leaders of the “monkey wrench gang.” And like Einstein, he was one of the gifted few who had the courage to tell the emperor the truth about his new clothes.

—Frank Voehl, Deming: The Way We Knew Him (p. 3)

You have heard the words; you must find the way. It will never be perfect. Perfection is not for this world; it is for some other world. I hope what you have heard here today will haunt you for the rest of your life. Then I have done my best.

- Dr. W.E. Deming, Newport Beach Deming Management Seminar, February 24-28, 1986

WELCOME to Doctor’s Orders #3, our new weekly series where you ask your most interesting or pressing questions about Dr. Deming’s philosophy of management, or anything Deming-related, and I do my best to find the answers!

Today, we’re going to return to a question by David S. from Doctor’s Orders #1 about Dr. Deming’s thinking on monopolies. David recently responded to the post and makes some points I thought warranted a second look at this topic. See if you agree!

Thanks for your comments on my post, David! This is a challenging topic, and I don’t think I’m going to win you over with this post, but it may serve to start transforming your thinking over time.

Let’s begin:

Old Economics, New Economics

As I read through your comments contesting Deming’s views on competition and monopolies, it occurred to me that much of the reconciling you were doing was because you’re reaching for an advanced level concept before grappling with and developing your own understanding of the fundamentals of Deming’s theory. In other words, you were interpreting “New Economics” words and concepts through an “Old Economics” lens: you read the words “transformation”, “competition”, “monopoly” and translate and decode them into meaning that is informed by deep habituation over a long period of time. That’s the state we all begin in, and it’s why I liken getting through it to being able to see through “The Matrix” — you’re forever changed once you take the proverbial red pill.

Thus, common words and ideas have entirely different meanings to Deming, eg. “transformation” isn’t something an organization undergoes, it is the process an individual goes through when they deconstruct old ways of interpreting phenomena and ideas like “adversarial competition” and replace it with new knowledge and meaning guided by a reliable theory. It is far stickier and more durable, and is neither quick nor linear.

So, what follows are my attempts to elevate where I think you need to study to build your knowledge, if your aim is to transform your thinking.

System of Profound Knowledge

For example, you say:

I find Deming’s view of monopoly to be rather strange… because it’s one of the very few aspects of his System of Profound Knowledge that are not backed up by available data.

Deming’s views on monopolies aren’t an aspect of the System of Profound Knowledge, which was his theory for transforming management thinking to better understand the daily phenomena we encounter in organizations. Scholtes called them “New Competencies”.

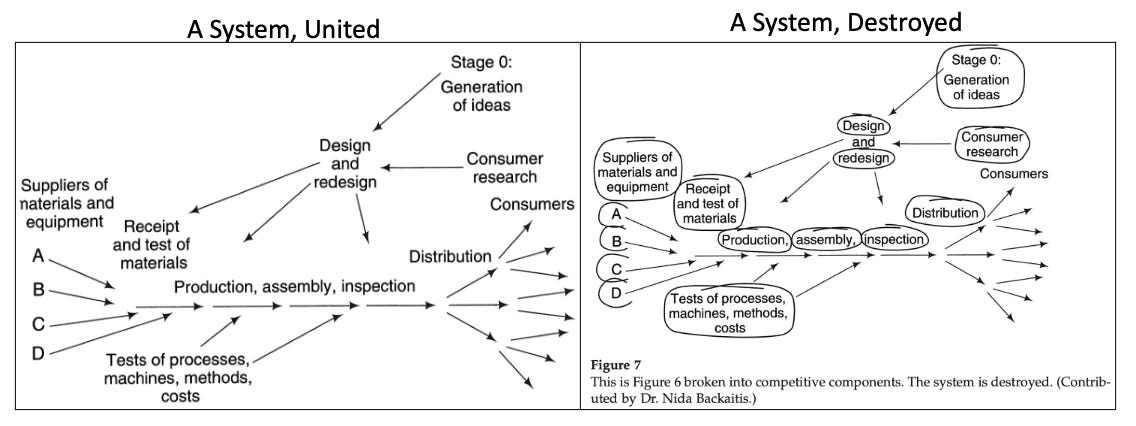

His views on monopolies come from his thinking on systems, how they are best-led, the effects of adversarial competition on the components of a system, and why systems need to be managed toward cooperation.

His influences on the effectiveness of well-managed and led monopolies would have come from his time working with Dr. Shewhart at Bell Labs and seeing the remarkable innovations they brought to market, including the precursor to the Integrated Circuit chip. There’s a reason he lamented, “We no longer have a telephone system. We have telephones.” - it can be found in The New Economics, Ch. 3:

Adversarial Competition, Cooperation

You next say:

[H]e asserts that competition is destructive and such destruction should/can be avoided in a monopolistic context; and he asserts that monopolies enable the reduction of competition which he says can lead to ‘Win/Win’.

Deming does say adversarial competition is destructive and should be avoided in favour of cooperative competition, ie. where all participants work together to elevate each other by improving the quality of their goods and services and creating and expanding markets rather than fighting over a share. While he implies there will be less adversarial competition for a monopoly to contend with, there is instead cooperation. This comes from his view that a monopoly is no different than any other organization that needs to be led as a system for the long-term benefit of all, from employees to society.

In The New Economics, he relates this short story from William Ouchi’s book, The M-Form Society about a keynote he delivered to an American trade association at their annual 3-day retreat on the difference between them and their counterparts in Japan:

Last month when I was in Tokyo, he explained, I attended meetings of your direct competitors. 200 companies, tiny and huge, working together as a system—working on design of products, export policy, tests of instruments, so that anybody’s oscilloscope would agree with his customer’s analyzer. They worked from eight in the morning till nine at night, 13 hours a day, five days a week: reached consensus after some months of labor.

Who do you think will be ahead five years from now, you or your Japanese competitors?

New Economics - 3rd ed. (p. 40), 2nd ed. (p, 55)

Key takeaway: A system includes competitors, but good ones who help each other to improve. Lousy competitors are selfish because they are not led as a system.

Edit: For a complementary read on Win/Win, see my Sept. 22/23 newsletter, Is The Deming Management Method Socialist?

Transformation Does Not Include the Status Quo

You go on to say:

There’s no evidence monopolies behave better, on average, than other companies. There’s no evidence that monopolies are immune to the problems Deming argues are inherent in the prevailing style of management. In the audio clip, Deming suggests that monopolies would benefit most by “keeping prices low” - but it’s pure fantasy to think monopolies would behave this way.

Dr. Deming would, I believe, agree with what you’re saying with one main exception: He never argued for maintaining the status quo. Not even a little bit. The word “transformation” in his lexicon doesn’t have shared meaning to what’s bandied about on LinkedIn today: It meant a complete departure toward a new system of thought.

So, in The Old Economics, where both types of firms, monopolies and independents alike, are led with a view to optimizing parts in the short term for maximum profits the aim is to “set the price as high as the market will bear and get out… make a big profit and get out”. Antitrust function here would be to protect society and educate the leadership on why this is detrimental.

In The New Economics, a monopoly has an entirely different aim and purpose: to be of maximum service to the world. This means being led and managed as a system, which includes employees, customers, suppliers, the environment, communities, and onward. Pricing would set for the long-term optimization of the system for everyone to win.

Key takeaway: Study theory of a system.

Large Systems Dynamics

Next, you explain:

Perhaps a few things have been learned about large systems that contradict Deming’s opinions about monopolies. For example. [John] Gall would argue that large systems suffer a higher friction quotient; their sensory mechanisms are limited and they become incapable of receiving market feedback; large systems produce large problems; and so on.

Again: Deming would agree with what you’re saying, but with the exception that he never argued for doing so while maintaining the status quo. “Transformation is required!”, as he’d say. Also, with respect to Gall’s observations in Systemantics, I think Deming would enjoy them enormously and have a few to add of his own. Incidentally, Gall doesn’t speak about friction of large systems per se, but a preference for them to be “loose” so they last longer and function better.

Of course, Deming advised leaders of very large organizations with equally large systems with thousands of employees, suppliers, vendors, stakeholders, and more. He saw every business as part of a larger whole with ever-increasing boundaries. In The New Economics, he explains you could draw a boundary around a simple production system in Japan and expand it to eventually include the entire nation.

But you raise interesting questions for me: When does a system become large? At what size does a system become “selfish” if unmanaged?

Key takeaway: Keep going on studying systems!

Market Share, Expanding the Market

Finally, you contend:

In the audio clip you shared, Deming derides the way companies chase “market share” - he argues this is an unhealthy symptom of [adversarial] competition in the market. But available data would show that Toyota competes for market share against other Japanese companies (Honda, Mazda, Isuzu, etc.] AND against American and European companies (GMC, Audi, Tesla) YET the quality and capability of Toyota (as a company) continues to advance. I’d argue, a market open to new entrants and [adversarial] competition has required they find ways to employ people at competitive rates, and deliver higher quality products at lower prices. (Win! Win! Win!)

Did you listen to the full clip? Here’s what he said:

Three automotive companies in this country had together in 1960 a virtual monopoly. The management of the three companies spent their time worrying about shared market. There’s our piece of the pie. Our piece is this big. How can we make the piece bigger? Worrying about share of market. What would have been better? … While the three automotive companies sat by and worried about each other, a million people needed automobiles. The automotive companies sat by and worried about share of market. Not expansion of the market. What they should have done is sat together and worked on expansion of the market. The Japanese came and did it. And Americans squealed and squawked.

You could make an argument for Tesla doing exactly this by expanding the automotive market to include luxury EVs, which in turn caused others in the market to create EVs of different types and capabilities - it’s not cooperative competition, but it is doing what Deming advised. Which is odd, because Tesla has about zero Deming management DNA.

Question: What is the aim of Toyota, as a company? Does their expressed aim and constancy of purpose include phrases like “dominate the market by any means to put others out of business or acquire them” ? How has Toyota affected other auto manufacturers? Suppliers? Vendors? Partners? Society?

I’ll leave this for you to investigate and consider.

Key takeaway: Keep studying effects of adversarial competition, the Forces of Destruction, managing with a view to optimizing parts, and how this extends into the organization and to what effect.

Japanese Monopolies and Coerced Cooperation

One more thing; you make mention of Japanese industry being successful because they were compelled by nationalistic/protectionist policies to cooperate. This doesn’t quite align with my understanding, so you may have a leg-up on me. In my view, the Japanese had no alternative but to cooperate after the war: their entire industrial centre from Yokohama to Tokyo was bombed until as flat as a pool table. They literally had to start from scratch, and were very receptive to the ideas of Deming, Juran, Sarasohn, Protzman, and Polkinghorn.

From what I gather, part of the US commitment to rebuild the post-war Japanese economy required disbanding the family-owned cartels, called zaibatsu, and opening up the economy for independent entrants. This was backed up by the introduction of the Anti-Monopoly Act in 1947, which still exists to this day. Over time the zaibatsu was replaced with a loose cartel arrangement called keiretsu.

A unique feature of keiretsu is the requirement for member companies to own shares in each other’s businesses to help avoid takeover attempts and buffer against market shocks with the aim to enable each participating firm to concentrate on long-range planning and execution. Very Deming-like.

Key takeaway: Read John Willis’ book, Deming’s Journey to Profound Knowledge for more on the history of what happened leading up to the Japanese miracle.

Summing It All Up

As I said at the outset, I’m pretty sure you’re still going to take issue with Deming’s thinking on adversarial competition and monopolies, and my aim here wasn’t to transform you, but to untangle and clarify your understanding and contrast it with my own. It’s my sincere hope you keep grappling with the material and your own assumptions when looking at the world through the lenses of The Old Economics and The New Economics.

What Do You Think?

Do you agree with David’s position? Is Deming wrong on all accounts, or is this a case of New Economics ideas viewed through an Old Economics lens? Do you agree with my interpretations and takeaways? What would you recommend instead? Let me know in the comments below or on our Chat thread for Doctor’s Orders #3. And, as always, keep an eye out for a Chat link next week where you can post your questions for the next instalment!

There is a ton to unpack in your posting, so let me just address one issue: adversarial competition.

This is simply a redundancy; the concept of cooperative competition is a huge stretch, and the Book "Co-Opetition" is not excluded.

The opposite of cooperation, two or more people working together for a common goal, is not competition. The opposite of competition is conflict, which is two or more people fighting to achieve a single goal.

Competition is just conflict with rules.

In competition there are winners and losers and it is the search for scarcity. If there is not a natural scarcity, we make one up; grades, trophies etc so we can compete. Cooperation is about win-win and creating something larger than what you start with where everyone benefits.

Deming gave examples of how the auto companies in Japan would cooperate by sharing information through JUSE for example, but they did that so they could compete on the world stage.

The concept expressed in the book “Co-Opetition” was to cooperate and compete. But if you look at what happens they cooperate within a sector, so that sector can better compete with some other sector supplying the same products. It was not about doing away with competition and the problems of competition -- but to use cooperation as a means so you could compete better.

Very little of this was addressed by Dr. Deming and his treatment leaves a lot to be desired.

He says that competition was bad but should be used in a few circumstances. As I recall he mentioned new product and new services yet failed to explain why these were exceptions. At the same time he failed to explain what was good about competition yet lauds the Japanese for their ability to compete in the world market.

What I see people doing is just following the writings of Deming without questioning it at all and this is one ripe case.

I am convinced there is a place for competition, a healthy place. Yet competition is, like behaviorism itself, a broadly believed-in concept where people have failed to address the downside.

In the end all competition is adversarial, at its heart it is conflict.

Incredible explanation! What I didn't realize until reading Deming is monopolies are not the problem; evil is the problem, greed and exploitation is the problem. Eliminating monopolies doesn't solve the problem of greed and exploitation, it just slightly hinders a situation it can take advantage of. We still have poor-quality goods and services and exploitative practices anyway.

Deming was talking about a total transformation, beginning with the heart and working outward. Quality is love, and when you love your neighbor and become a servant to them (everyone is your customer), quality comes naturally. It is entirely possible for a monopoly to be a monopoly just because they provide the greatest goods and services.

Just look at VALVe, their online video game store "Steam" is virtually a pseudo-monopoly because everyone loves their customer service so much. Gabe Newell famously said that media piracy is a mostly a problem of bad customer service, and he sought to fix that. So when ads for a class action lawsuit against Steam were going around recently, Steam customers were mocking them for it in the comments. It's an amazing thing to see.