WELCOME to the first of our new open Q&A series on all things Deming-related, Doctor’s Orders, where I gather questions submitted on a weekly basis via Chat and do my best to answer them. In today’s post I take on questions about Deming’s views on monopolies, joy at work, and the elimination of bonuses and commissions.

Let’s get started…

Trivia: The title for this segment comes from a UK TV show Dr. Deming was interviewed on in the 1980s.

Q1: Why does Deming speak so highly of monopolies?

Our first question is a banger and it comes from a friend and colleague in the agile community, David S., who also provides this context:

Background: I believe monopolies are negative forces in society and an enemy of free markets. Like capitalist economists advise, I believe the emergence of monopolies should be limited by sound antitrust legislation and market regulations that encourage competition and reduce start-up costs.

Thanks for the tough question, David! On the face of it, it does seem rather odd that the man who inspired the Japanese miracle that would out-compete American auto manufacturing at its own game would hold monopolies in high esteem, but there is some internal logic to why he maintained this position, rooted in his thinking on systems and particularly competition.

Contrary to the prevailing views of free-market economists and HR managers, Deming sharply disagreed on the merits of adversarial win/lose competition as a universal solvent for all problems, seeing it successful only at dissolving a higher-order behaviour, cooperation, within and between organizations. As he says on page one of The New Economics:

We have grown up in a climate of competition between people, teams, departments, divisions, pupils, schools, universities. We have been taught by economists that that competition will solve our problems. Actually, competition, we see now is destructive. It would be better if everyone worked together as a system, with the aim for everybody to win. What we need is cooperation and transformation to a new style of management.

Deming held that were economists to know even a little about the theory of a system, “they would no longer teach and preach salvation through adversarial competition, [and] instead lead us to the best plan for a system”. He called his vision of cooperative competition, “win/win”, and is such a radical concept for those who have been conditioned by The Forces of Destruction (see Q2, below) as to appear to promote socialism, which, believe it or not, he was accused of in one of his 4-day seminars. So, it’s not surprising in the least that his position on monopolies would be similarly understood in the other direction.

For Deming, monopolies represented a well-optimized system that, unfettered by win/lose competition, “has the best chance to be of maximum service to the world, and has a heavy obligation to do so.” Consistent with his teachings, this requires “enlightened” leadership who can manage the monopoly as a system, ie. in accordance with an aim for everyone to benefit over the long-term, not just themselves and shareholders. With this freedom, the monopoly could focus on improving the quality of their operations, products, and services for the betterment of society.

Idealistic? Altruistic? Possibly, but then, he wasn’t wasting his time advocating for how to keep the prevailing style of management on life support while tinkering with fixes here-and-there. For Deming, transformation meant transformation.

It naturally followed that in this context, a monopoly would not want to set prices “a cent higher than would optimize… the whole system”, which would be tantamount to “cheating themselves out of profit in the long run”. The function of the Antitrust Division, in Deming’s view, should be there to educate and explain this principle for extracting maximum benefits from monopolies and cartels, and to safeguard against those who have a demonstrated inability to learn.

Of course, Deming’s view on monopolies sharpened considerably after the 1984 breakup of Bell Telephone, the former home of his friend, mentor, and inventor of the control chart, Dr. Walter Shewhart. He lamented: “We no longer have a telephone system. We have telephones.”

In sum, it’s understandable why it seems that Deming was making an incongruent argument for monopolies—it’s not what we’ve been taught. But, there is much we have been taught that ain’t so. Nevertheless, as he says in the audio clip below, we can learn something different.

Suggested Reading & Listening

Is The Deming Management Method Socialist? (Sept. 22/23)

The New Economics, 3rd ed (pp. 51-53), 2nd ed (pp. 73-75)

The Essential Deming (pp. 30-34)

Hear Deming explain his entire view on monopolies, price fixing, and antitrust in this excerpt from one of his presentations to General Motors in 1992:

Q2: Why can’t we have joy at work?

Dr. John C. asks our next question and straightaway we know he’s talking about Dr. Deming’s oft-repeated phrase, but with a twist substituting “at” for “in”. Intentional?

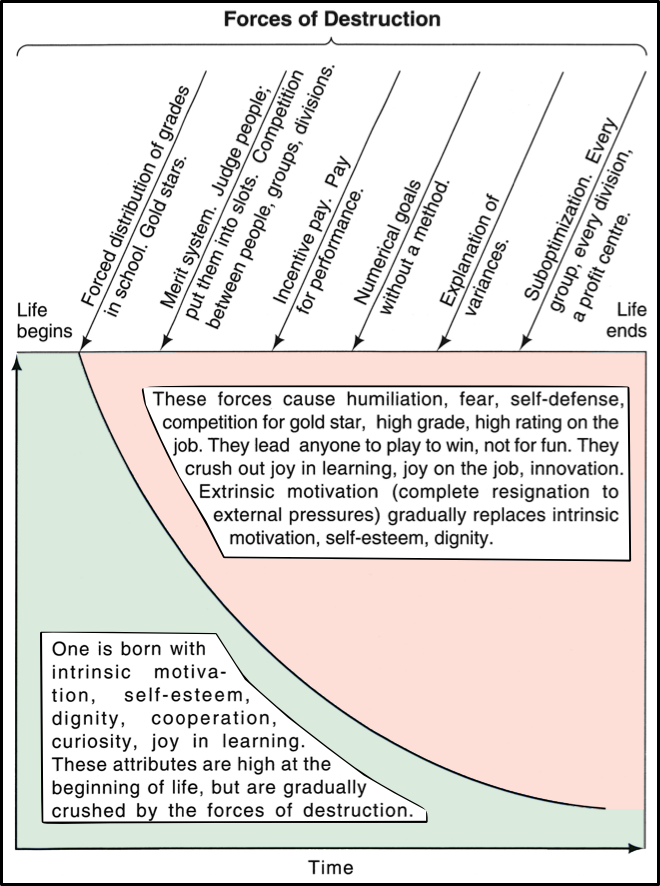

Regardless, I share Dr. Deming’s perspective here: We cannot have joy at work because we have deliberately designed it out of our society and institutions by conditioning people to accept replacement of their innate positive qualities like curiosity, intrinsic motivation, cooperation, and joy in learning with negative traits like fear, cynicism, defensiveness, competition for advantage over others, and increasing dependence on extrinsic motivators.

Deming called this process “The Forces of Destruction” (see below) and held its cumulative effects responsible for our declining fortunes.

As time progresses, the green shaded area yields to the red as the forces wear the individual down into accepting this is "just the way things are”. The professional disillusionment created is so pervasive in our culture as to be cliché — we willingly believe that every job will eventually become just that: a job. The work will no longer be the reward, and the focus narrowed to the next appraisal.

Paradoxically, some managers are left bewildered by how difficult it is to encourage teamwork under these conditions. It leads to bizarre situations as I encountered in one engagement where I was asked to help a “team” learn about agile delivery practices only to discover most of the members reported to different managers and had skills that weren’t even complementary. They were literally a collection of co-located people who happened to work on the same project from time-to-time. No joy in work could be found there.

Suggested Reading:

The Forces of Destruction (Mar 2/2023)

Q3: What are the potential impacts to the business if management eliminates all employee incentives, especially for those in sales?

Our last question for today comes from Munavver F. via Substack Chat which I’m interpreting as “What are all the downsides for eliminating pay-for-performance and sales commissions?”

Good question! Deming spoke forcefully about the damage incentives do to a system, but less so on some of the consequences you can expect when you change compensation: for him, the benefits far outweighed the problems, and what problems emerged would be good ones to have, eg. building a better system based on cooperation and joy in work.

This said, if management just eliminates all incentives and commissions without clearly communicating why, nor a plan for what to replace them with, you can predict what happens next: chaos ensues, people leave, business suffers. This is called tampering, and it leads to creating cycles of increasing problems.

However, even if management does everything right and starts with open and honest communication about the change, explains the rationale and benefits, and alternatives to replace performance pay, there can still be some who will find they can’t or won’t do the work without a carrot to chase or a peer to best, such is the conditioning power of The Forces of Destruction. What then? Be content and patient: better people will assuredly come your way who want to be a part of a system where they can focus on their work, not their paycheque.

I have found that those who are most successful at avoiding the negative fallout from moving toward a salary-only compensation structure typically adopt a formula like:

Existing Compensation + Maximum Achievable Bonus = New Compensation

and then pair this with annual profit-sharing and/or fixed awards for years of seniority and/or contributions to system improvements and teamwork.

In any event, the main takeaway here is to not make compensation decisions in haste without understanding the theory about why you want to eliminate incentives and explaining your position to employees, and what you propose to do instead.

For an entertaining read about a leader who made the leap and what happened next, check out the link to Dr. Henry Neave’s Twelve Days to Deming Day 6 training unit below about Jim “Matress Mack” McIngvale.

Suggested Reading

Salaries Over Commissions (Aug. 25/21)

Remove Barriers to Pride in Workmanship (Jun. 24/22)

What Can We Do Instead of Appraising People? Oct. 23/23)

Neave, Dr. Henry: Twelve Days to Deming - Day 6: Gallery Furniture and Other True Stories (PDF)

Scholtes, Peter. The Leader’s Handbook, Ch. 9: Performance Without Appraisal

Moesta, Bob. Demand-Side Sales 101: Stop Selling and Help Your Customers Make Progress

It’s a Wrap!

Doctor’s Order’s #1 is in the bag! What do you think? Did I raise more questions than I answered? What do you think I missed? Let me know in the comments below!

Also: Keep an eye out for a new Chat thread I’ll be opening up for submitting questions for next week’s Doctor’s Orders!

Good stuff Chris!

(Not knowing if there's a character limit here, I'll follow-up to the question about monopolies.)

I find Deming's view of monopoly to be rather strange.

## First:

Because it's one of very few aspects of his System of Profound Knowledge that are not backed up by available data. Likewise, Deming's view of competition is not backed up by data. For example, he asserts that competition is destructive and such destruction should/can be avoided in a monopolistic context; and he asserts that monopolies enable the reduction of competition which, he says, can lead to 'Win/Win'.

But I think these are faith-based claims rather than empirical claims.

Of course, if we look *only* at the activities in Japan at the time, then it may appear there's truth in those assertions. I understand the temptation to argue Japan's companies acted monopolistically, with cohesion, with cooperation, and *ta da* — look at the 'Win/Win' they achieved. They achieved high-quality products and improved Japan's economy tremendously!

But that's the wrong level of analysis. That's only half the story. Japan and it's various monopolies that Deming praises had fierce competition and a common enemy: the USA.

## Second:

The data tell us that the monopolies in Japan that succeeded (in part due to Deming's influence) were the result of extreme force: I'm referring to the nationalistic and protectionist policies that compelled (or "enabled" if you prefer) Japan's industrial giants to cooperate.

Worldwide, the data tell us that monopolies often sprout from innovative entrants in the free market (Apple in early 1980s, AT&T in 1880s), and those same monopolies often persist due to regulations, gov't subsidies, and protectionist policies that are hostile to younger/smaller competitors (Apple & AT&T 2020s, CBC in the 2020s, Air Canada, etc.). These sorts of regulations are predictable in what is called "late-stage" capitalism. Capitalism corrupts toward monopoly and economists (like Friedman) who prefer free market capitalism to other forms (such as "stakeholder capitalism" or "crony capitalism") argued that anti-trust regulations are necessary to preserve a free market that welcomes new entrants.

Is Deming in favour of such protectionist policy-making? Does Deming favour a "planned economy" wherein a government decides the winners of the monopoly game?

## Third:

There's no evidence that monopolies behave better, on average, than other companies. There's no evidence that monopolies are immune to the problems that Deming argues are inherent in the prevailing system of management. In the audio clip, Deming suggests that monopolies would benefit most by "keeping prices low" — but it's pure fantasy to think monopolies would behave that way. Case in point: the government of Canada is a monopoly and it's getting more costly by the day — they have zero incentive to keep prices (i.e. taxation) low.

## Fourth:

Perhaps a few things have been learned about large systems that contradict Deming's opinion about monopolies. For example, Gall would argue that large systems suffer a higher fiction quotient; their sensory mechanisms are limited and they become incapable of receiving market feedback; large systems produce large problems; and so on.

## Fifth:

In the audio clip you shared, Deming derides the way companies chase "market share" — he argues this is an unhealthy symptom of competition in the market. But available data would show that Toyota competes for market share against other Japanese companies (Honda, Mazda, Isuzu, etc.) AND against American and European companies (GMC, Audi, Tesla) YET the quality and capability of Toyota (as a company) continues to advance. I'd argue, a market open to new entrants and competition has required that they find ways to employ people at competitive rates, and deliver higher quality products at lower prices. (Win Win Win!)