No concept has been more misunderstood by American managers, academics, and workers than productivity. For workers in America a call for increased productivity carries with it the threat of layoffs. Managers understand productivity to be an economic trade-off between efficiency and product quality. Business-school courses on management are often watered down to numerical games of inventory control and production flow in which financial budgeting and tight control are oversold as effective management tools.

(Yoshi Tsurumi, American Management Has Missed the Point—the Point Is Management Itself)Deming, W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis (The MIT Press) 2nd Ed. (p. 147), 3rd Ed. (pp. 124-125). The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

THE AIM for this brief newsletter is to share and analyze through a Deming lens a recent OpEd in Canada’s Financial Post on the lagging productivity of our country’s construction industry. It is written by an Associate Dean of Graduate Programs and Urban Analytics at Toronto Metropolitan University and a real estate industry veteran who combined have some observations and diagnoses for what ails us, firmly embedded in the prevailing style of management.

What this article shows is how we almost never question the water that keeps everything in suspension, ie. the prevailing ways we’ve become habituated to think about everyday phenomena in our organizations, and in this case, country. We just look right through it. We can change this to a better habit by adopting a Deming perspective.

Backgrounder

Here in Canada, we are facing a rather desperate housing crunch: we simply cannot build new, affordable housing fast enough to keep up with demand, especially as our immigration intake soars over 1M per year. Our leadership in Ottawa have set a lofty goal of 3.87 million new homes built by 2031, but in accordance with the tenets of the prevailing style of management, haven’t suggested the methods this could be achieved, or whether this was within the capability of the broader “system” of construction.

As the OpEd authors relate, previously, the problem was thought to be a lack of skilled trades that was holding back our new housing starts, however, the latest hiring statistics suggest that despite a 136% increase in workers since 1997, new housing starts haven’t kept pace at 63%. A classic example of what Dr. Deming would call tampering with a system through over-compensation, as he showed with Rule 3 of the Funnel Experiment.

Further, a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. report cited in the article observed that from 1999 to 2004 “workers per housing start” were lower than they are today, suggesting that we have (drum-roll, please) a productivity problem. Of course we do, it’s widespread and we’re not yet aware of what to do about it in any sector or industry because we’ve not had awareness of what to do differently.

Proposed Solutions

The authors propose a range of solutions, including:

Increasing the size of construction firms through mergers and acquisitions so they can take advantage of larger economies of scale and better deals on supplies, but totally ignores the consequences of mashing two different systems together.

Study past data and historical evidence to understand why housing productivity was higher in the 1970s and 1980s: a smart idea, but would need to be done with an eye toward system effects, not just local optimizations.

Examine the impact of red tape, NIMBYism (Not In My Back Yard activism, ie. efforts to curtail construction projects because they would affect existing property owners), and development charges. I’d file this with studying current system effects.

Collaboration between government and industry to find solutions. Perhaps the smartest solution, along with finding all the barriers that get in the way.

Absent from the list is looking at the “system” of construction as a whole in Canada to better understand what the current capabilities are and whether any of these suggestions can contribute to meeting the goal, ie. are they even system improvements or local sub-optima like a misguided government program?

For our purposes here, I’m going to limit our focus to understanding the construction system through the data we have about how we are doing and what our present capacity is and whether the goals that have been set are achievable by the system.

Scale of the Productivity Problem

Some time ago I put together some Process Behaviour Charts to look at our new home construction capacity in Canada using data from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, a government-owned Crown Corporation that compiles data on housing, in addition to other financial solutions and government program delivery.

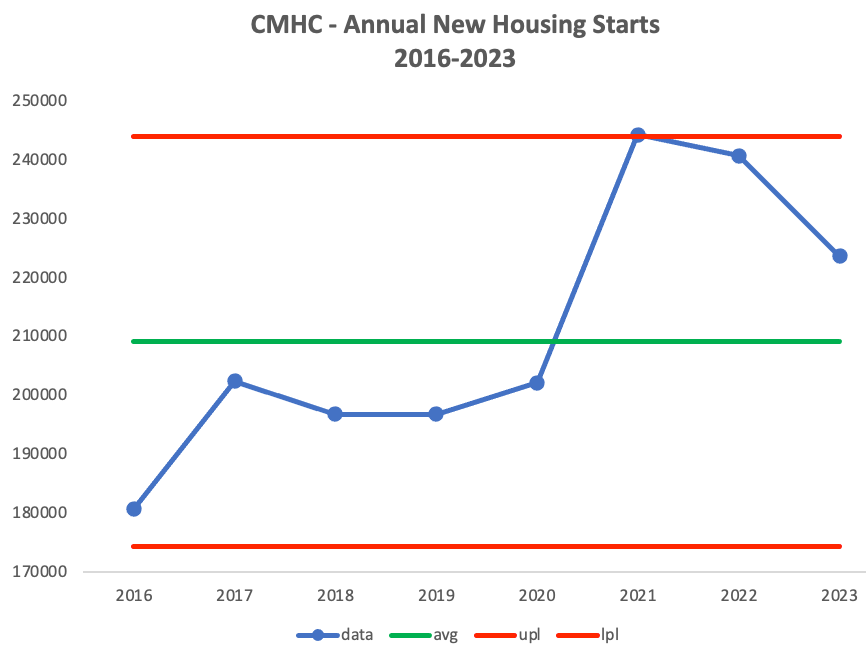

Recall the goal the government has set is 3.87 million new homes by 2031, or about 552k per annum. That naturally provokes the question of how many homes our system is currently capable of delivering. As shown in the PBC below, the past eight years of annual starts suggest a stable system with 2021 as a stand-out year going slightly above the upper 3σ limits. This could be attributed to pent-up work from the first year of the pandemic response, with an echo-effect in 2022. 2023 starts to look more “normal” in the context of the other data points:

NB: the upper process limit at 243k sets the boundary for the system against a baseline period of 2016-2022, which is well-below the 550k to meet the government’s goal. Recall that in a stable system the variation of the data points is defined by the upper and lower process limit lines which are calculated as estimates above and below the mean. This means the annual target is beyond our system’s current capabilities.

While this isn’t surprising, so far no one in either the media, industry, or government has expressed the problem in these terms, which is required if we’re going to address it effectively.

So, let’s go a bit deeper into the data: what do the monthly figures tell us?

Apparently, a lot: we can see there is a seasonal pattern to our system’s output, with the nadir almost every January and the apogee almost every July, with the exception of 2021 when it was in November — a clue on why it was such a banner year.

Given our climate, this makes a lot of sense. We can see that for the baseline period of June 2020 to December 2022 we have a mean of 19.9k starts/month with upper and lower limits of 26.1k and 13.7k respectively, predicting the range of future starts.

We also see some signals that could be investigated, like why the starts from April-November 2022 are all above the baseline mean, or why the starts for January 2022/23 fall below the lower process limit for the same baseline period.

However, what would system’s output need to increase by per month to meet the 550k/year target? I did some Excel spitballing and through trial-and-error found we would need to boost the current monthly figures by about 230% to get close to the annual target:

This arrangement, mapped to the current data, would produce the following annual starts:

In this hypothetical model, the Canadian home construction system would need to produce an average of 45k homes per month, with corresponding process limits of 60k and 31k to match the pattern of variation in the original figures. Let’s illustrate this more starkly by moving the data points back to their original values but keeping the upwardly-adjusted mean and limits for comparison:

As shown, the limits for the target system are well beyond the current system’s capabilities, presenting us with our challenge: we need to improve the system so we can move all those dots up and into the projected limits.

Improving Productivity

Earlier this year I wrote an open letter to the Sr. Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada who was on a speaking tour for business leaders about the necessity to boost our nation’s lacklustre productivity as a bulwark against future inflationary shocks. She returned to economic theory of the past for ideas like Capital Intensity, Labour Composition, and Multifactor Productivity. “New” ideas such as those proposed by Dr. Deming that helped to turn the Japanese economy around didn’t even make a footnote.

In a subsequent newsletter, The Productivity Trap, I explain how to think about productivity as a lever that transforms systems output according to where you move a fulcrum along a continuum of quality: everything you do to improve the quality of your processes and the interactions between the constituent components increases the “mechanical” advantage, giving you outsized results for your inputs:

NB: A single quality improvement by a chosen system measurement can be comprised of many individual but complementary changes to one or more processes over time. It can include clarifying operational definitions, the preparation of upstream work items/product to eliminate downstream rework or confusion, narrowing suppliers down to those that produce the highest quality products with the least variation, or removing adversarial competition and fear, and other faulty practices of management.

Rx? As Dr. Deming would advise, begin with understanding the aim of the system and its parts. Draw a map of the components and how they are interrelated: How well do the components work together? Who depends on what from whom, in what state and on what schedule? What effects do the current interactions have on productivity? How could the quality of these interactions be improved?

What processes or interactions could we improve to move toward the goal of increasing productivity? Should one part of the system be sub-optimized in the short-term so that another can achieve a longer-term improvement? How will we know a change has yielded an improvement? By what method?

These are the questions that need some thought by those who own the system and components. A little study of Dr. Deming’s theory could pay some outsized dividends, here.

Summing it Up

My aim with this newsletter post is to provide an alternative view of Canada’s new home construction problem and how it’s much more complex than presented in the media or thought about in the various levels of government. It requires a new way of thinking that Dr. Deming’s theory can help unlock.

For example, with the knowledge of Appreciation for a System and Variation from his System of Profound Knowledge, we can quickly understand what we need to do to test whether a numerical goal is attainable by first plotting the system data on a Process Behaviour Chart and seeing whether all the points are within the limits and if we can reasonably predict future performance with them.

As I’ve shown above, our new home construction system follows a seasonal pattern that is 230% below where we would need to be to meet the government’s target—well beyond the current process limits. So far throwing more money and labour at the problem hasn’t worked, and instead has likely has exacerbated the problem, contributing to an over-supply of workers that are a net-drag on productivity. A systems solution is required, which means looking at the quality of the interactions between the components to move our fulcrum and increase our “mechanical advantage”.

However, this begs the question: can Canada writ-large work together as a system? I’m not hopeful - and I’ll explain why in an upcoming newsletter issue.

Reflection Questions

Consider the problem of new housing starts as I’ve presented in this newsletter:

What components and relationships would you add to the incomplete system map I sketched above?

What system impediments can you think of that would either hold the quality fulcrum in place or move it backward that would need to be overcome? How?

What role(s) should each level of government, Federal, Provincial, and Municipal play to improve productivity?

What changes to the system would you predict would yield outsized gains in new housing starts?