An Open Letter to the Sr. Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada on Productivity

If Japan Can, Why Can't Canada?

Dear Sr. Deputy Governor Rogers:

I recently watched with considerable interest your March 26, 2024 speech to Halifax Partnership where you outlined the Bank of Canada’s urgent call to action for Canadian business to begin addressing our long-standing, poor record on productivity as a bulwark against future inflation. You correctly observe that we seem to be going in reverse, with the past six of seven consecutive quarters showing a decrease in our quarterly productivity figures, and an overall 17% contraction in our economy’s productivity compared to the US from 1984 to 2022. As a Canadian small business owner I share your concerns and agree the time has come to “break the emergency glass”—it’s actually well past—and take a serious, hard look at what we can do to reverse our decline. As a student of Dr. W.E. Deming’s theory of management, I have some insights that I think can help and build upon some of the suggestions you made, which I will explain below.

Early in your remarks, I was encouraged to hear you allay the concerns of your audience that the task at hand won’t require working longer or harder under the same conditions but by finding ways to multiply the output of every hour worked for the same or less effort—effectively a lever that could provide outsized productivity gains. However, you also explain that despite much study, there’s been no consensus on the causes for our lagging productivity, nor a single “silver bullet” solution we could use to turn things around. Nevertheless, under pressure to act you suggest we go back to traditional economic theory for answers, to concepts like Capital Intensity, Labour Composition, and Multifactor Productivity.

I propose to you that there is another path we could take almost immediately with what we have, at little cost, that would have an outsized impact on our nation’s productivity, and was instrumental in reversing the fortunes of a war-ravaged country: Quality.

The Chain Reaction for Improving Productivity

In 1950 an American statistician, Dr. W. Edwards Deming, traveled to Japan to teach their business leaders, managers, and engineers how to increase their productivity by focusing on improving quality first. He taught them that as quality improves, productivity naturally follows and costs decrease as causes of rework, mistakes, delays, and waste of machine-time, labour, and materials are reduced or eliminated.

He presented this to them as a chain reaction:

What does “Improve Quality” at the start of this sequence of events mean? It does not mean increasing inspections, haranguing employees to pull their own weight and do a better job, putting up inspirational posters, adopting “best practices” you read about in Harvard Business Review, implementing more rigid procedures, or creating executive roles responsible for quality assurance. It is an attitudinal shift in thinking from leadership on down to direct all efforts toward improving the quality of their products and services by improving the quality of all activities and interactions behind them. Why? Because employees cannot achieve more than top-management will allow, and they are the most responsible for how their organizations work. As Dr. Deming once explained, quality is made in the boardroom, and as a colleague once said to me, it is un-made there, as well.

Incidentally, this isn’t far-removed from the appeal to leadership you made in your talk with respect to equipping employees with more reliable tools that don’t break easily (causing lost time and increased expense) and can augment their capabilities for every hour worked. This is just one aspect of leadership’s responsibility for quality, however.

Production Viewed as a System

Adopting a commitment to improving quality first requires a commensurate shift in thinking about how production works as a system of interdependent components with a defined purpose or aim rather than a chain of command with direct reports in various divisions. This encompasses the entire production line and organization from inbound materials through to delivery to customers who may provide feedback on whether their needs are being met by the provided product or service and may influence future iterations or innovations.

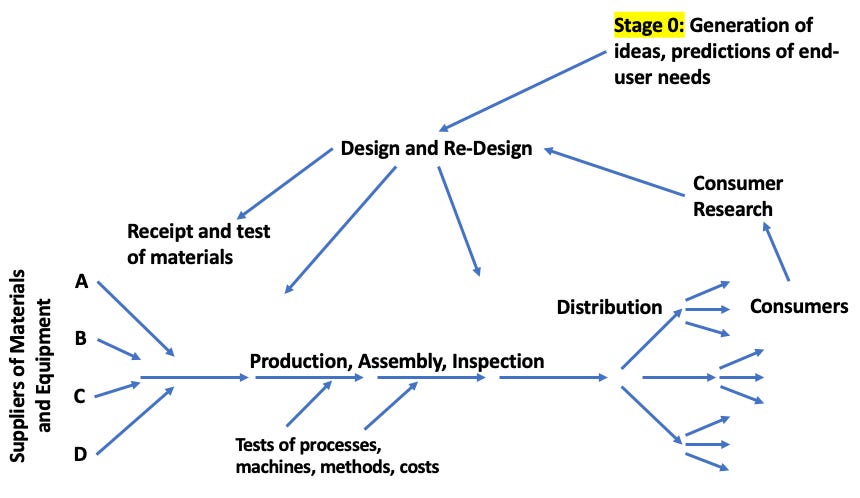

Dr. Deming explained this with a flow diagram:

This is a model for operationalizing the Chain Reaction for improving quality and productivity that is easily transferrable to any type of business. You could begin to use this by placing names at each stage to envision who depends on whom for what and in what condition to do their job, and how this is improved when care is taken to appreciate how one’s work is used by others. So viewed, quality permeates throughout the production line, directed toward creating continually better products and services for customers.

At the time, and even today in modern-era Canada, this whole-system view of quality and productivity improvement stands in stark contrast to the prevailing thinking that quality is inspected or audited at the end of production rather than built-in from the start. We see and experience the consequences of this every day, wherever an LRT breaks down or tracks are mislaid, an aircraft suffers mechanical failures, software applications malfunction, medical procedures or tests are delayed or go awry, new household appliances break, a municipality mistakenly issues a massive tax bill, or a payroll system fails in its mission, there are myriad processes where quality can be improved and are instead being remedied with rework and workarounds. And the implications for this extend well beyond the affected customers, cascading all the way into our productivity figures.

The Japanese Miracle

What Dr. Deming began by teaching the Japanese the causal linkages between quality and productivity and how to operationalize it throughout their organizations by viewing production as a system ignited a renaissance for their economy. He famously said that by following his advice and learning new theory, particularly about how to manage quality by understanding how to “see” variation in how processes work, they would have the world’s manufacturers screaming for protection in five years. They did so in four. By the 1960s they were invading more and more markets with higher quality products, and by the 1970s American auto manufacturers found themselves for the first time unable to compete with Japanese imports in terms of quality and features. This came to be known as the “Japanese Miracle”, for which Deming received a high honour from Emperor Hirohito in 1960, but went largely unnoticed in his own country, until a fateful summer day in 1980.

If Japan Can, Why Can’t Canada?

On June 24, 1980 an NBC aired a documentary hosted by news correspondent Lloyd Dobyns that aimed to reveal the causes behind the decline of American industry and rise of the Japanese that could well describe the situation we face in Canada forty-four years later, almost word-for-word. Entitled, “If Japan Can, Why Can’t We?” it outlined the condition America found itself after the OPEC oil crisis, unable to match Japanese quality in fields it once dominated, their productivity mired in inefficient processes and government regulations, adversarial, non-cooperative relationships between business and government, and excess consumption.

Dobyns opens the documentary in a manner that echoes your speech about Canada’s productivity predicament:

This program is about the strongest most productive economic force the world has ever known, the United States. We have been for a long time. There are reminders of that here in the Smithsonian's Museum of History and Technology. The question is not what have been or are now, but what we will be. For the first time our productivity is not increasing.

Productivity is not some esoteric economic subject: it is how much we produce and how much it takes to produce it. The object is to make more for less; if you do, everyone benefits.

In the last fifteen minutes of the program Dobyns interviews Dr. Deming to learn what he taught the Japanese which I urge you to watch yourself. It was in these moments that he suddenly had the attention of American industry, and at the age of 80 found himself in high demand to teach the theory and methods he had taught the Japanese decades earlier. He would do so for the next thirteen years, but only on condition that top-management go first.

At the end, Dobyns asks Deming whether the same methods would work in the US, to which he replied: “Why of course we could! Everybody knows we can do it. We have no idea about the right thing to do. We have no goal.”

The question for us, then, is: if post-war Japan could do it, why, with all our blessings and head-start, can’t Canada?

Rx? Learn the New Philosophy, Encourage Its Adoption

I’ll conclude with an appeal for you to consider what I’ve written here as the beginning of a blueprint for revitalizing Canadian productivity through the improvement of quality with the aim to punch well above our weight. In your capacity with the Bank of Canada you could provide direct leadership on this effort first by learning more about Dr. Deming’s management philosophy and theory, and subsequently by teaching others in your speeches and visits across the country. In so doing, if we are united in this aim as a nation, I believe we can replicate the Japanese miracle and eclipse our competitors within five years.

Should you want to learn more, I would be happy to go into more detail about what I have described here via Zoom or phone call. You can reach me via my LinkedIn profile, here.

Sincerely,

Chris. R. Chapman,

Publisher, The Digestible Deming Newsletter (Est. 2021)

Where to Start?

This newsletter - which is searchable. Start with keywords like quality, system, production;

Deming’s books: Out of the Crisis, The New Economics

The Deming Institute’s self-paced, online learning portal DemingNEXT.

The Deming Institute’s video collection on YouTube

Miro Board with Notes

For my paid tier subscribers, you can access my Miro board with my notes that contributed to this letter. It contains a lot of material that ended up on the cutting room floor as it evolved. Be aware I may be reformatting and adding material after this post is published.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Digestible Deming to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.