Systems Primed for Finding Fault

Everyone Is Already Doing Their Best

Example. On arrival at the Nashua Tape Company in Albany, New York, I saw in the conference room a number of men working with deep concern. The problem? Rejection of a roll of paper (weight one ton) at the end of the line, ready to be slit, a catastrophic loss. The men were working on the process, trying to improve it so that this catastrophe could not happen again.

On a previous similar catastrophe, a few years earlier, the procedure was very different. The superintendent of the operation pinned the blame on some unfortunate man. Punishment: (1) censure, disgrace, the cause of the problem: (2) no more overtime for him; (3) job changed to dirtier work.

The difference between the two ways to handle the catastrophe was striking. What happened between the two events that could cause such a difference? The answer lay in the manager, by name, Mr. Bob Geiger, and the change that he wrought in the management of people. One of his first remarks to me when I first met him was rebuke of his management for paying to him a bonus. “If they have to pay me a bonus to make sure that I do my job, I ought not to have this job in the first place.”

Deming, Dr. W.E. The New Economics, 3rd ed. (pp. 88-89)

It is not enough for everyone to do his best. Everyone is already doing his best. Efforts, to be effective, must go in the right direction.

Deming, W. Edwards; Deming, W. Edwards. The Essential Deming: Leadership Principles from the Father of Quality (p. 7). McGraw Hill LLC. Kindle Edition.

Statistical techniques, based as they are on the theory of probability, enable us to govern the risk of being wrong in the interpretation of a test. Statistical techniques defend us, almost unerringly, against the costly and demoralizing practice of blaming variability and rejections on to the wrong person or machine. At the same time, they detect almost unerringly the existence of a special cause when it is worth searching for.

Deming, W. Edwards; Deming, W. Edwards. The Essential Deming: Leadership Principles from the Father of Quality (pp. 248-249). McGraw Hill LLC. Kindle Edition.

THE AIM for today’s post is to re-examine the prevailing phenomena of blame as a corrective management action through a Deming lens, and consider what we could do instead. We first looked at this in my July 14, 2021 newsletter, Who’s to Blame? which you can refer to for some additional context.

It is brought to mind by the recent FAA crisis that delayed or cancelled over 11,000 flights in the US. Given how our prevailing mode of seeing the world as individual nodes and not networks of interdependent components has primed us, we are directed to find out who was responsible and why:

An engineer 'replaced one file with another,' an official told ABC News, not realizing the mistake was being made and ultimately causing the system to show problems and fail. The culprit engineer has yet to be identified. Engineers and IT teams are working feverishly to prevent the system from crashing again today, as they also scramble to figure out if there are any similar systems that could fail as easily…

An official told the outlet, 'It was an honest mistake that cost the country millions.'

Source: Daily Mail, January 12, 2023

The US Federal Aviation Administration has blamed the computer outage that caused a massive disruption on "personnel who failed to follow procedures."

Source: DW, January 13, 2023

EDIT: After publishing this post, I found additional stories that unsurprisingly laid fault on an individual for not following procedures. This will surely bring a wry laugh to anyone familiar with Dr. Deming’s Parable of the Red Beads, which we explored in my September 10, 2021 newsletter.

While we don’t know the engineer’s fate, we can presume given all the attention so far that he may well spend some time away from his duties while the organizational systems he worked within might be subjected to a localized post-mortem for what to blame. Remediations will be made to local processes, of course, but what about the antecedent decisions that led to creating them in the first place? Will the systems of management that designed the protocols that contributed to the fault undergo similar inspection? We will probably never know. However, we do know, per our earlier exploration of blame, we can reasonably expect 97% of issues to belong to the system, 3%— to special, outside causes.

Systems Primed for Blame

Deming contemporary and management consultant, Peter Scholtes, writes in the first chapter of his 1998 book, The Leader’s Handbook, about the possible origins of the “modern” hierarchical management structure as a consequence of an investigation into why two Western Railroad trains collided between Worcester, Mass. and Albany New York on October 5, 1841.

Recommendations from a Massachusetts legislative committee traced fault to the haphazard structure and management system of the railway, and a model drawn from the Prussian army was advocated that would influence organizational structures for decades into the future. It will be immediately familiar to most:

Benefits of the model, as described by Scholtes (p. 3), included:

Centralized offices run by “managers” (a new term for the time)

Distinct functional divisions

A “chain of command” with clear lines of authority

Clear lines of communication and reporting.

Clear descriptions of responsibility for each individual, top to bottom.

The president of the Erie Railroad, Daniel McCallum, would later add these expansions on the advantages of this model (emphasis mine):

A proper division of responsibilities.

Sufficient power conferred to enable the same to be fully carried out, that such responsibilities may be real in their character (that is, authority to be commensurate with responsibility).

The means of knowing whether such responsibilities are faithfully executed.

Great promptness in the report of all derelictions of duty, that evils may at once be corrected.

Such information, to be obtained through a system of daily reports and checks, that will not embarrass principal officers nor lessen their influence with their subordinates.

The adoption of a system, as a whole, which will not only enable the General Superintendent to detect errors immediately, but will also point out the delinquent.

As Scholtes observed:

A fundamental premise of the “train-wreck” approach to management is that the primary cause of problems is “dereliction of duty.” The purpose of the organizational chart is to sufficiently specify those duties so that management can quickly assign blame, should another accident occur.

(p. 4)

Ergo, we have for many decades subscribed to a model of organizational design that is finely-tuned to attribute system faults to individuals in absence of their interdependencies, besides those that flow vertically on a direct-report basis. A lot of information is deliberately excluded from this model.

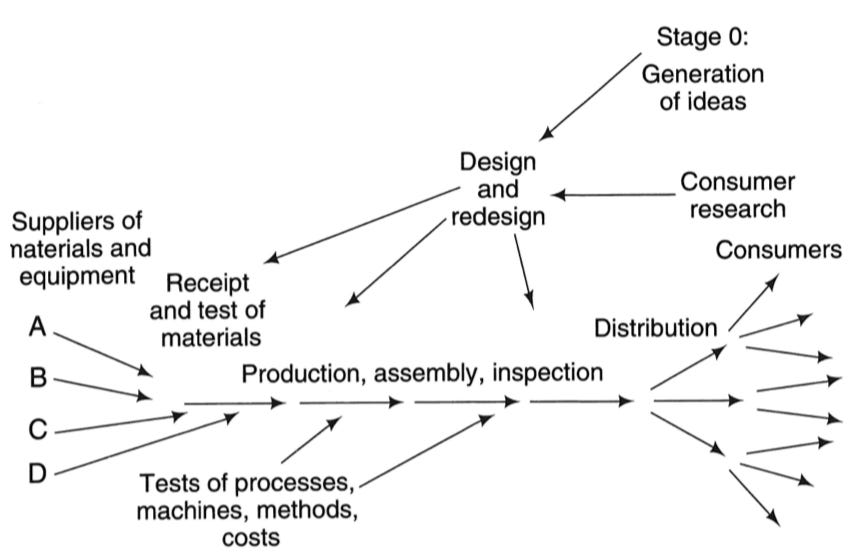

Compare and contrast that model with the one proposed by Dr. Deming to the Japanese in 1950, viewing production as a system to explicitly show the interdependencies between various stages and roles. Were you to place names on this chart of who does what, and when in your organization, you’d likely find the same names recurring in multiple places. You’d also find there are multiple nested systems, each dependent on the other. This is profound knowledge:

Suppose we were to draw a similar structure for the organization our hapless maintenance engineer works within: how many interdependencies might we find? What protocols was he following for replacing the file? Who is responsible for updating them? How are they tested?

Culture Follows Structure

An old adage in my line of work advises leaders that the culture they are observing in their organization is downstream of the structure they are responsible for managing. If the structure is based on rewards and punishments, we can reasonably expect the culture to demonstrate commensurate dysfunctions. Who wants to be the straw that broke the camel’s back in this environment?

If we design and adhere to structures that are designed to affix blame when things go wrong, we cannot be justifiably surprised when problems arise. How does a culture centred around quality or innovation emerge within this? Conversely, within the same system, what happens when things go right? Is similar effort dedicated to understanding why, or is it accepted as the prescient wisdom of leadership? You cannot have it both ways, at least not with some intellectual honesty and humility.

What to Do, Instead

In Katie Anderson’s thoughtful and powerful 2020 book, Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn: Lessons from Toyota Leader Isado Yoshino on a Lifetime of Continuous Learning, she describes the profound relationship between her and her mentor, Isado Yoshino, and the leadership lessons he impressed upon her through a series of stories. In one story, he relates what happened early in his career at the Motomachi Paint Shop when he made a mistake in the ratio of mixing auto paints with solvents, causing the paint to not stick on over 100 cars and causing delays.

Yoshino immediately knew that he had made a mistake when doing his task. He remembers that first moment: I was so scared. I thought, “Are they going to fire me?” My mistake created a huge problem — they would have to repaint all those car bodies!

Much to Yoshino’s surprise, instead of immediately shouting at Yoshino or blaming him for the 100 cars that would have to be repainted, his manager instead calmly asked, “What did you do?”

Anderson, Katie. Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn: Lessons from Toyota Leader Isao Yoshino on a Lifetime of Continuous Learning . Integrand Press. Kindle Edition.

Yoshino demonstrated his process and the manager immediately identified the problem: He had confused cans of paint and solvent because they were nearly identically-labeled with small, hard-to-read text.

Upon seeing and hearing all of this, not only did Yoshino’s boss not blame him for the mistake, he apologized for not setting up the work environment so that a mistake like this would not have been so easy to make! Yoshino describes his surprise about the Paint Shop manager’s response: My boss did not blame me directly, which made me feel so relieved. Instead he said, “Don’t worry, mistakes can happen. You are just a beginner and you did your best. Thank you very much for making this mistake, as we are so familiar with the process here in the Paint Shop that we didn’t label the area very clearly. I am sorry.”

Anderson, Katie. Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn: Lessons from Toyota Leader Isao Yoshino on a Lifetime of Continuous Learning . Integrand Press. Kindle Edition.

Note the bias Yoshino’s boss had to first observe the actions that contributed to the problem, then to reflect on what within the shop’s processes could permit an employee to make this mistake, and finally to apologize to the worker for the error along with a commitment to fix it. Fear, which Yoshino certainly had, was immediately dissipated and leadership as a quality, stepped in.

Yoshino observes:

“Blaming is your power as a boss. But if you start with blaming, it is hard to go back. It may make you feel temporarily happy, but is not good in the long run.” …

When I look back now to where I learned how to be a people-oriented leader, I realize that it started with this experience in my first months in the Paint Shop. It was my first encounter with Toyota leaders. Their reaction to my mistake showed me the Toyota culture — and the type of leader I wanted to be.

Anderson, Katie. Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn: Lessons from Toyota Leader Isao Yoshino on a Lifetime of Continuous Learning . Integrand Press. Kindle Edition.

Everyone Is Already Doing Their Best

Dr. Deming would frequently remind attendees to his seminars and leadership he was coaching that everyone in their organizations are already contributing their best efforts: improvement would only come from working on the system. Leadership who possessed this view, he argued, would be unable to sustain a culture of fear and blame because they would have profound insight into the root causes of defects as predominantly residing in the system they were responsible for managing.

Reflection Questions

How is the phenomena of blaming or attributing fault managed in your organization? Consider the quotes from Dr. Deming above, Peter Scholtes’ explanation of train-wreck management, and the story of Isado Yoshino at the Motomachi Paint Shop: Does your management follow the philosophy of blaming systems before people, or is HR primed and ready for official reprimands and hasty exits? How have errors been corrected? By “demoting” people to dirtier work, or by helping each other improve?

What structures do you believe contributed to the good and bad behaviours? What might you try to implement, instead? How would you go about introducing the change to the prevailing culture and gauge results?

Consider our hapless engineer who overwrote the wrong file: what responsibility does management have for the error? What contributions to the system could be made? Where should they come from? Who should make them?