11b. Eliminate numerical goals for people in management. Internal goals set in the management of a company, without a method, are a burlesque. Examples: (1) Decrease costs of warranty by 10 per cent next year; (2) Increase sales by 10 per cent; (3) Improve productivity by 3 per cent next year. A natural fluctuation in the right direction (usually plotted from inaccurate data) is interpreted as success. A fluctuation in the opposite direction sends everyone scurrying for explanations and into bold forays whose only achievements are more frustration and more problems.

- Deming, Dr. W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis (MIT Press) (p. 75). The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

As you'll remember, the management stated that unless this fourth day were substantially better than the other days that they'd close the place down, sweep it out. But somebody in the management came through with a fantastic suggestion, a new style of management, magnificent! Instead of closing the place down, they're going to keep it going with the three best workers!

- Deming, Dr. W. Edwards, Red Bead Experiment with Dr. W. Edwards Deming. (5:42)

Goals, aims, hopes. How could there be life without aims and hopes? Everyone has aims, hopes, plans. But a goal that lies beyond the means of accomplishment will lead to discouragement, frustration, demoralization. In other words, there must be a method to achieve an aim. By what method? …

Futility of a numerical goal. A numerical goal accomplishes nothing, as already noted. What counts is the method--by what method? It is good to remember the admonition from Lloyd S. Nelson (Out of the Crisis, p. 20). If you can accomplish a goal without a method, then why were you not doing it last year? There is only one possible answer: you were goofing off.

- Deming, Dr. W. Edwards. The New Economics, 3rd ed. (pp. 29-30).

LAST WEEK I had the privilege of attending Eric Budd’s Institute for Quality and Innovation Virtual Academy, a four-month program that he facilitates to teach the Deming management philosophy to new (and experienced) managers. This week was focused on the psychology domain of Dr. Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge, and I was on-tap as a guest presenter for the unit on intrinsic motivation which went (I think!) really well. Reviews have yet to trickle-in, but I digress…

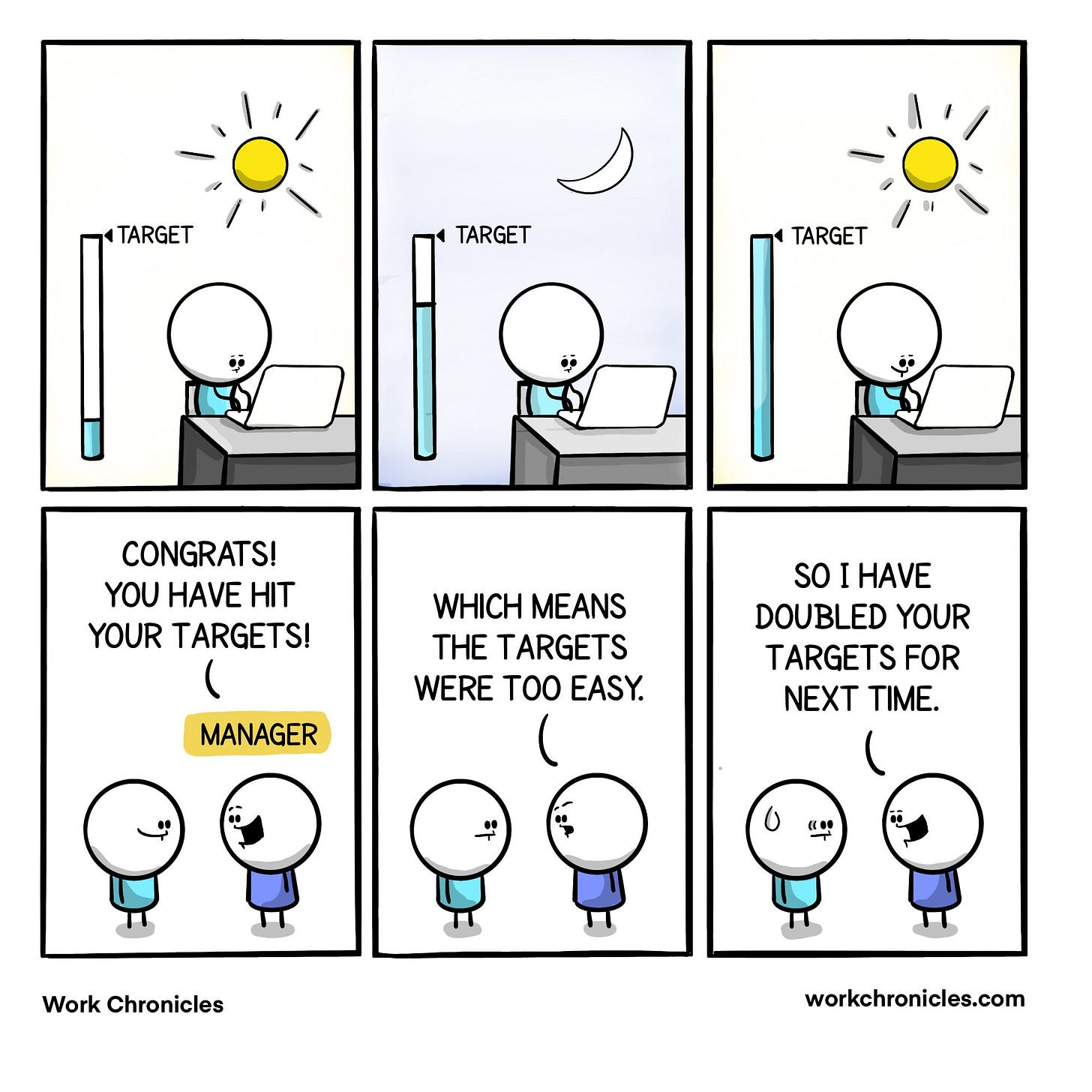

On the day prior to my session, we reviewed a classic video of Dr. Deming facilitating the Red Bead Experiment at one of his four day seminars back in the 80s, and coincidentally, I stumbled on the above Work Chronicles management cartoon that suggested a hand-in-glove pairing for today’s post as it perfectly captures what happens to the “best” willing workers in the demonstration: They earn themselves double-shifts. I think this a salient lesson to reflect on as we rush headlong into year-end trying to “make” our Q4 numbers before the holidays.

We also had homework given at the end of class to view Dan Pink’s 2009 TED Talk on The Puzzle of Motivation in preparation for the next day’s class. Pink delivered this talk at the time he was promoting his now-classic book, Drive, and the “scientific” discoveries that were made on what motivates us in work and life, including the catchy triumvirate of Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose. One of the more salient takeaways was the inverse relationship between effectiveness of incentives and the intellectual demands of the work we’re engaged in doing, as shown by Dan Ariely’s experiments at MIT. He demonstrated that when the work requires little-to-no intellectual effort, just rudimentary or rote tasks, increasing incentives produced commensurate changes in output, but as soon as there was a little intellectual effort required, it backfired.

Pink’s work has been a touchstone for those of us in the agile/lean coaching community, and we’ve taught his and other like-minded researchers’ and consultants’ theories on why not to use carrots and sticks to “drive” changes in outcome for over a decade. This is nothing new, of course: Frederick Herzberg wrote about it in his classic 1968 HBR paper, One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees? noting that the common-sense management consensus of the time was to apply KITAs or Kicks in the Ass to move people toward goals rather than unlock motivation to achieve them. He was thinking about intrinsic motivation before it was “cool”.

In particular, Herzberg has insightful observations that are very Deming-aligned with respect to understanding how having meaningful work is a better motivator than using incentives. He distinguishes three concepts: Job Enrichment, Job Enlargement, and Job Loading.

Rather than rationalizing the work to increase efficiency, the theory suggests that work be enriched to bring about effective utilization of personnel. Such a systematic attempt to motivate employees by manipulating the motivator factors is just the beginning.

The term job enrichment describes this embryonic movement. An older term, job enlargement, should be avoided because it is associated with past failures stemming from a misunderstanding of the problem. Job enrichment provides the opportunity for the employee’s psychological growth, while job enlargement merely makes a job structurally bigger…

Job loading. In attempting to enrich certain jobs, management often reduces the personal contribution of employees rather than giving them opportunities for growth in their accustomed jobs… Job loading merely enlarges the meaninglessness of the job.

- Herzberg, Frederick. “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” September-October 1987 Harvard Business Review. (p. 10).

In 1987, he reprised his paper and noted in his reflections twenty years hence the first publication that despite all the knowledge and advancement gained through efforts of organizational behaviourists, they were no further ahead in changing management thinking and behaviour:

Today, we seem to be losing ground to KITA. It’s all the bottom-line, as the expression goes. The work ethic and quality of worklife movement have succumbed to the pragmatics of worldwide competition and the escalation of management direction by the abstract fields of finance and marketing – as opposed to production and sales, where palpable knowledge of clients and products resides. These abstract fields are more conducive to movement than to motivation. I find the new entrants in the world of work on the whole a passionless lot intent on serving financial indexes rather than clients and products. Motivation encompasses passion; movement is sterile.

- Herzberg, Frederick. “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” September-October 1987 Harvard Business Review. (p. 17).

This came to mind for me with some pathos as I re-watched Pink’s enthusiastic delivery and exasperation at the “mismatch between what science knows and business does”: and here were are, thirty-four years hence Herzberg’s reprised paper, and a dozen years hence Pink’s books and talks. We have mountains of evidence, even games to make intrinsic motivation apparent (like this one I shared with Eric’s class during my session which incorporates Pink’s observations, among others) and yet, we’re no further ahead. We still fall back on flawed common-sense to guide our thinking.

Reflection Questions

Consider the quotes from Dr. Deming above and the role of incentives in management-by-caprice (ie. without means or methods, just reactive reasoning and application of so-called common sense). In what ways could you, in your immediate sphere of influence, change the thinking around you on attaining goals and the applicability of extrinsic motivation to drive behaviours? In your opinion, what theory or hunch could you test to make a change toward improvement?

Take a look at Dan’s video and read Herzberg’s paper on HBR that I’ve linked in his above quote. In your opinion, what are they getting right? How durable have their observations been in comparison to what you’ve seen and experienced at work? What stands in the way of designing systems and work that encourages intrinsic motivation?