Overjustification

The Subtle Art of Robbing People of Their Pride

An award in the form of money for a job done for the sheer pleasure of doing it is demoralizing, overjustification. Merit awards and ranking are demoralizing. They generate conflict and dissatisfaction. Companies with wrong practices pay a penalty. The penalty can not be measured.

Rewards motivate people for rewards.

- Dr. W.E. Deming. The New Economics, 3rd ed. (p. 77)

To clarify overjustification, I relate here an example told to me by Dr. Joyce Orsini.

A little boy took it into his head for reasons unknown to wash the dishes after supper every evening. His mother was pleased with such a fine boy. One evening, to show her appreciation, she handed to him a quarter. He never washed another dish. Her payment to him changed their relationship. It hurt his dignity. He had washed the dishes for the sheer pleasure of doing something for his mother.

- Ibid. (p. 75)

Examples of overjustification. A man, not an employee of the hotel, picked up my bag at the registration desk of a hotel in Detroit, carried it to my room. The bag was heavy. I was exhausted and hungry, hoping to get into the dining room before it would close at 11 p.m. I was ever so grateful to him, fished out two dollar hills for him. He refused them. I had hurt his feelings, trying to offer money to him. He had carried the bag for me, not for pay. My attempt to pay him was, in effect, an attempt to change our relationship. I meant well, but did the wrong thing. I resolved to be careful.

Ibid. (p. 76)

IT is a holiday Monday here in Canada as we observe Labour Day, which seems an appropriate backdrop for our topic du jour of overjustification. I was also inspired by a recent Tweet a colleague in the Agile community offered the other day:

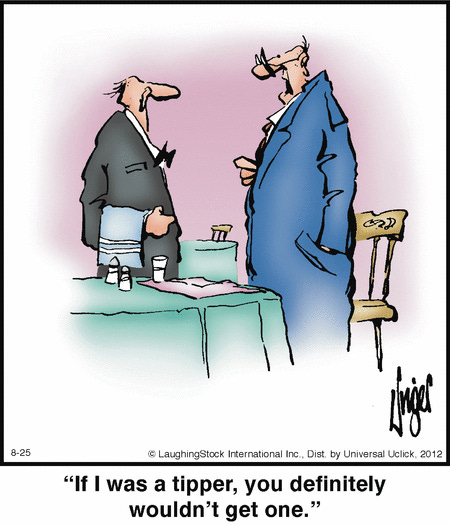

In the West, giving people “extra” money for their efforts is a baked-in behaviour we learn while we’re young, and likely was a source of our income in early jobs. It also becomes a source of rancour when used as a means to communicate our pleasure or displeasure, as John Lithgow hilariously demonstrates in this clip from the 90s sit-com, 3rd Rock from The Sun:

While satirical, Lithgow’s performance is funny precisely because he is pointing out the absurdity of our ideas on systems of reward - and I am sure Dr. Deming would have a chortle over it as well as we see the joy in work evaporate for the server. Tips become a shorthand for communicating our pleasure or displeasure with service of a system, which the server bears the brunt.

However, for Dr. Deming, the effects can be a little more insidious when we presume that the only way someone would do a task for us is for monetary reward. We’ve become so inured with the notion that all work is unenjoyable that the idea of offering a “bonus” is the least we can do. It also distorts and diminishes the relationship between people.

As an example, Dr. Deming describes a scenario in The New Economics where, as a sign of his appreciation to his doctor, sent him a personal note of thanks for how he treated an infection along with a cheque for his services:

I encountered him by chance one day, weeks later. The cheque we had both forgotten, but the letter? No. He had it in his pocket. It meant a lot to him, he told me, to know someone cared.

Two years later, when I went to see Dr. Sh in Washington, he remarked to me in passing, “I ran across Dr. Dv the other day: he asked about you.”

What if I had added five dollars to the Dr. Dv cheque in appreciation? That would have wounded him. That would have been a horrible example of overjustification.

A good plan of appreciation, I submit, would be to donate a sum of money to a hospital dispensed under the guidance of Dr. Dv for medical care for patients that can not pay.

The New Economics, 3rd ed. (p. 77)

In our own organizations, we encounter overjustification all the time, mostly because we do not understand how to organize our systems of management to leverage intrinsic motivation. And so we see the proliferation of “on the spot awards” which may be dispensed at management’s discretion, or in a fit of magnanimity, by other employees to recognize their fellows. In either event, the consequence is a diminishing of the relationship and an open acknowledgment that the process of improving the work so pride can be restored won’t be happening any time soon.

An Example of an Alternative

Some years ago I attended a conference for agile coaches here in Toronto where participants were encouraged to offer notes of recognition (they were called Kudos Cards) to others who had inspired them either with a talk they gave or a personal one-on-one interaction that led to some epiphany. I received one from a young woman for whom English is a second language, that expressed her appreciation of my use of language and words in my conversations and presentation because it helped her learn new words and phrases to improve her use of English. This formed a bond between us that has lasted to this day where we exchange notes about new words we’ve discovered over Twitter or when we run into each other at various meetups. What if she had offered a Loonie ($1 coin) ? I don’t know if we’d still be in touch…!

Reflection Questions

As we always do, review Dr. Deming’s thoughts on the subtle concept of overjustification and use them as a lens to interpret your thinking on this form of reward and consequences. What examples can you think of from your past experiences or those of others, that demonstrate how a well-intended gesture went awry? What could have been done differently? Is it possible to change an entrenched behaviour just by stopping it, or does something need to take its place? How are low-value rewards, like on-the-spots, used in your organization? Why were they given? In recognition of going above-and-beyond what? Has the contrivance led to improvements for everyone?