New Competency #1: Systems Thinking, Systems Leading

And so we begin...

The degree of interdependence between component processes may vary from one system to another… A bowling team has low interdependence because it is composed of individual members whose scores are added…

On the other hand, a fine orchestra is highly interdependent. The players are not there to play solos as prima donnas, to catch the ear of the listener. They are there to support each other. They are usually not the best players in the country. They work as a team under the leadership of the conductor…

Management’s job is to optimize the entire system. Suboptimization is costly. It would be poor management, for example, to optimize sales, or to optimize manufacture, design of product, or of service, or incoming supplies, to the exclusion of the effect on other stages of production.

- Dr. Deming as quoted from one of his seminars in Latzko and Saunders, Four Days with Dr. Deming. (p. 35)

Management’s job is to coordinate the activities of each component. It is their task to see to it that the activity of each component contributes to the aim of the system. Failure to achieve this coordination can optimize one or more components at the expense of the total system. Component optimization often results in system suboptimization.

- Dr. Deming as quoted from one of his seminars in Latzko and Saunders, Four Days with Dr. Deming. (p. 36)

THE AIM for this newsletter is to explore the first of six new “leadership competencies” as explained in Peter Scholtes’ 1998 book, The Leader’s Handbook: The Ability to Think in Terms of Systems and Knowing How to Lead Systems. We first learned of the new competencies and the old ones that precede them in my Nov 1/23 newsletter, The New Competencies.

This competency is the foundation upon which the entirety of Dr. Deming’s philosophy on management rests and the gateway to understanding it. When you develop a deep appreciation for how your organization or business functions as a system, many of the commensurate changes in thinking that Deming advises will reveal themselves and fall into place one-by-one.

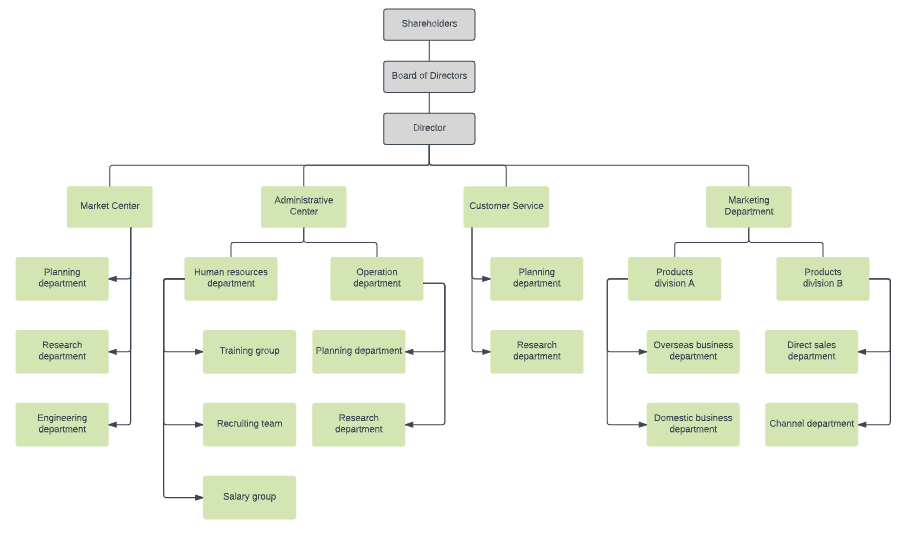

Following Scholtes’ lead, we begin by comparing and contrasting the prevailing way we think of organizations, the hierarchy, with Deming’s systems view and the implications for each. We’ll then look at the differences in how we think about leading a system vs. a hierarchy.

The Old View: Hierarchies and Train-wreck Management

Hierarchies are a defining organizational structure that is applied throughout our society and even in nature. You probably remember the taxonomic hierarchy from high-school biology class that organizes and stratifies organisms into increasingly specific categories based on their shared characteristics. The aim behind the structure is to provide a shared standard scientists and researchers can use to understand genetic connections between different species:

Domain/Kingdom—>Phylum—>Class—>Order—>Family—>Genus—>Species

Scholtes tells us in the first chapter of the Leader’s Handbook that the prevailing structure we use today to organize, stratify, and classify roles and specify who reports to whom originated in the aftermath of a railway accident in 1841 where two Western Railroad passenger trains collided. Cause was attributed to a lack of a proper chain-of-command structure with clear lines of reporting and responsibility in the organization like one would have in, say, the army. It was then recommended by a legislative committee that all railways adopt a management structure based on that used by the Prussian army so future train-wrecks could be prevented. The rest is history…

Scholtes goes on to explain that the fundamental premise behind the model is to classify duties from top to bottom so management could quickly identify who to assign blame or responsibility to when things go wrong, and ironically the next person up when things go right. In turn, this model would inspire a host of faulty practices Deming would warn about based on reactions to perceived signals of “failure”. In a way, every dysfunction we see in how organizations are led and managed today emanates from this structure: with such a limited view, it’s the only way it could possibly be managed…

Implications: Who is the Most Important Customer?

Look at any org chart and you will notice that it cannot tell you:

What products or services the org makes (could be anything, really);

How they get made (method? what method?);

Who depends on whom for what to make things happen (totally invisible);

How proximate departments are to one another, figuratively and literally (the map is not the territory);

Who the end customer is (you won’t see them at all).

As Dr. Henry Neave explains in the Deming Dimension:

The most important implication of the hierarchy diagram is that the most important customer of anything which goes on is the immediate superior of the individual or group concerned. In fact, of course, the most important customer should be the one who receives the fruits of the labours of that individual or group, ie. whose work is helped or hindered by them. Information, feedback, communication of any kind—exactly what is needed to aid improvement efforts—is indirect and inefficient unless some strong horizontal lines are drawn through the vertical structure. Those who should be the real internal suppliers and customers are otherwise effectively far apart from each other, whether or not they are physically so. (pp. 134-135)

Ergo, our “map” of the organization is too vague to be useful in helping us understand how we work together, for what purpose, and for whom. We need a new map…

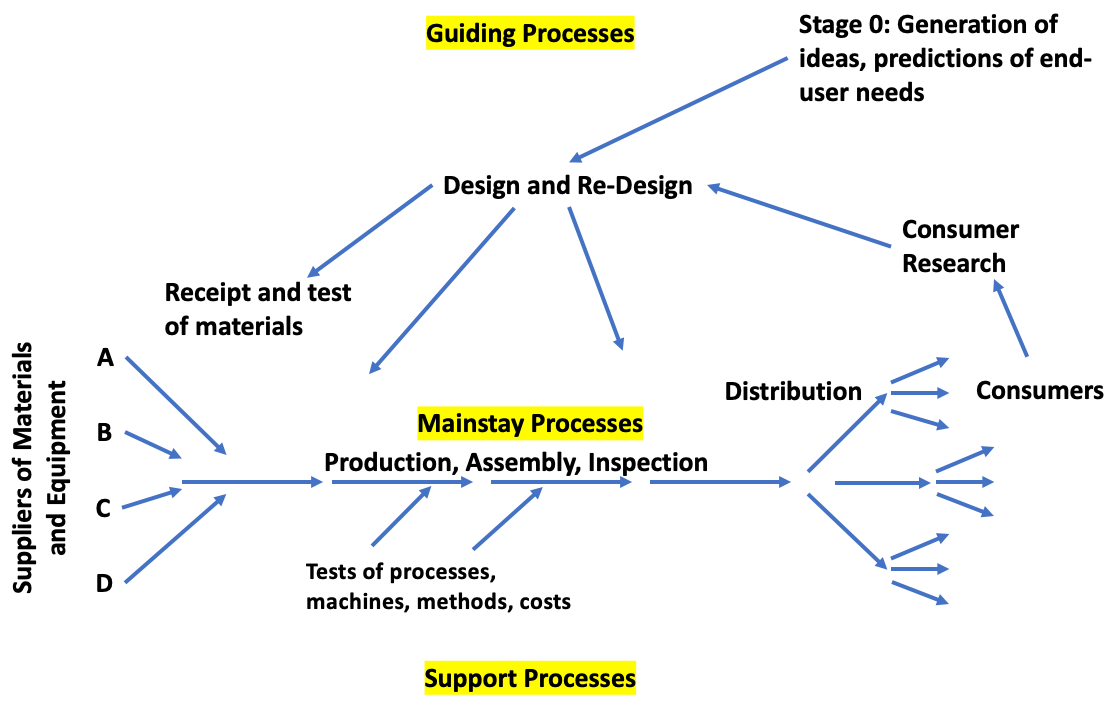

The New Map: Production as a System

In 1950, Dr. Deming drew the following diagram on a chalkboard while delivering his lectures to Japanese engineers and their management on how to improve quality. It showed, for the first time, a model of Production Viewed as a System of interdependent processes each linked to the next rather than an idealized hierarchical reporting structure of who reports to whom:

In contrast to the old vertical view, there are no role titles with reporting lines, dotted or otherwise. Instead, we see a horizontal flow diagram with inputs and outputs illustrating how products are envisioned, designed, developed, tested, and distributed to customers, and in turn how customer feedback informs research and future product iterations in a never-ending loop. In his first work on his philosophy, Out of the Crisis, Dr. Deming identified the customer or consumer that we see on the rightmost part of the map as the most important part of the production line.

This model has inspired countless others, such as this one that John Dues includes in his book Win-Win to illustrate how his charter schools in United Schools Network work as a system; note how he logically groups the parts:

Scholtes also provides his take, the SIPOC (see-pock) model in The Leader’s Handbook, making the system’s purpose explicit:

What is a System?

Before going further, as always, we need to set up an operational definition for what a system is in our context. There are almost as many definitions as there are systems, but let’s confine ourselves to two, starting with Dr. Deming’s — you should be able to commit this to memory:

A system is an interdependent network of components that work together to try to accomplish the aim of the system. A system must have an aim. Without an aim, there is no system.

The New Economics, 3rd ed. (p. x)

Note the emphasis on interdependence - each component, and that includes people, machines, tools, processes - have interdependencies which can be direct and line-of-sight, or subtle and intangible. Also note that a system needs an aim or purpose for existing. All operations of the system lean towards the aim. A good indication of a non-system is when the components have no interdependencies and function independent of one another for their own purposes.

Ackoff’s Definition of a System

In The Leader’s Handbook Scholtes enumerates Dr. Russell Ackoff’s eight characteristics of a system that we can use to expand on Dr. Deming’s definition, giving us more to mentally munch on. As you’ll see below, Ackoff was fond of using the metaphor of a car and transportation network to explain his thinking:

A system is a whole comprised of many parts (ie. a car).

The system unit has a definable purpose (eg. a car’s purpose is to provide personal transportation).

Each part of the system contributes to the system’s purpose, but no part by itself can achieve that purpose. (eg. an automobile engine cannot provide personal transportation by itself).

Each part has its own purpose. But when it affects the whole system it is dependent on other parts. The parts of the system are interdependent.

We can understand a part by seeing how it fits in a system. We cannot understand a system by identifying each part or the entire assembled collection of parts.

Looking at the interactions among the parts might help us understand how this system works. But to understand why this system exists, we must look outside the system, usually at human events and larger systems. (Why is the steering wheel on the left in some countries and on the right in others?)

To understand a system we must understand its purpose, its interactions, and its interdependencies. When you take a system apart, it loses its essential characteristics. Analysis involves looking at the parts. Synthesis involves looking at the whole.

When we look at an organization, we are looking at a complex social system as well as a technical system.

The organization has its interests, purpose, and interacting, dependent parts.

The organization is but one interacting, interdependent part within even larger systems (eg. the business, the industry, the economy, the nation, the world)

Within the organization there are interacting, interdependent parts, each of which has its interests and purpose that may affect, in a positive or negative way, the organization’s ability to achieve its purpose.

Organizations add the complexity of social interactions—relationships, teamwork, collaboration, cooperation, community, etc.—to technical and mechanical interactions.

Implication: Everything is Connected

The org chart is a very simplified and sanitized user interface over the reality of any organization it describes, quietly hiding (or even ignoring) the underlying complexity of the components, their interdependencies, and interactions. While easier on the eyes, it abstracts-away the reality behind daily phenomena: nothing occurs in a vacuum, everything is connected in one way or another.

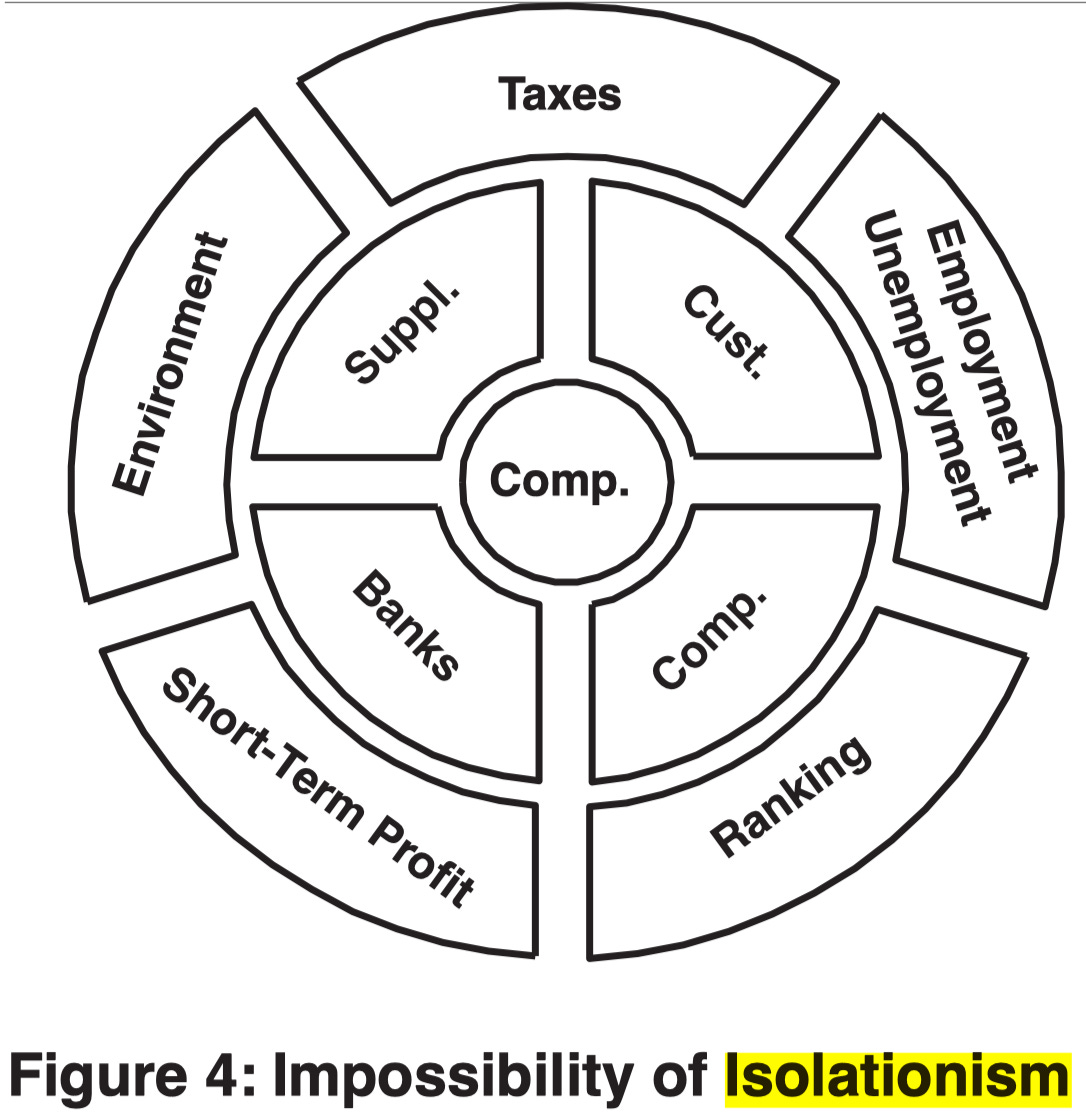

In The New Economics, Deming gives us a heuristic to better appreciate this: 94% of the effects we see in organizations are attributable to the way we’ve put things together in the system, 6% are due to special or extraordinary circumstances. Scholtes similarly elaborates in The Leader’s Handbook that any current situation we are experiencing in our organization is the product of the interaction and interdependence of multiple factors, forces, and events as shown in the following diagram:

Dr. Deming had a similar view that he’d share in his seminars to illustrate how, despite best efforts, a company or individual cannot become an island unto itself because they are subject to all the forces around them, something he called the Impossibility of Isolationism:

Remember again that a system is a network of components that work together for an aim, each contributing the maximum for the overall aim of the system… Consider somebody (or a company) who decides to become selfish, only concerned about himself—see Figure 4.

It’s impossible. He cannot do this, he cannot draw a ring around himself. For he is influenced by many forces that are part of the system, e.g. ranking—ranking people, plants, divisions, with reward and punishment… And other forces: taxes, reports, the bank working on short-term profit, the educational level of people, the environment, competition, the amount of employment and unemployment in the country, customers, suppliers. You cannot do this: you cannot draw a ring around yourself. You have to draw it without a ring. Whether you like it or not, they are all part of the system, and we need to optimize the whole system.

- Dr. Deming, as quoted in Swiss Deming Institute December 2006 Papers Collection (pp. 57-58).

Ergo, when we choose to see the organization through the lens of the org-chart, we miss a lot of the fine details behind the phenomena and focus on people as a first-order cause that needs to be fixed, rather than the processes and systems they work within.

Leading Systems vs. Leading Hierarchies

The main difference between leading with systems view as opposed to a hierarchy view is the appreciation that the causes of phenomena reside within the interactions between the parts rather than the parts themselves. We become less concerned about forcing the parts to work individually and more concerned about improving how they work together, even when they may not be functionally or physically proximate. We come to appreciate how a problem in one part can precipitate bigger ones in others. Planning takes on a very different character, where the way that discrete components and processes are linked together becomes critical to the work of improving what gets delivered to the customer. Moreover, we become preoccupied with defining a clear aim and purpose for our system that is broadly-shared and communicated to help sort out what we should be doing as opposed to what we are doing.

A good first step is to begin mapping a process flow you are closest to, detailing the main functional responsibilities, respective people who are responsible for each, and the work products that they create from upstream inputs. A good place to start is with Deming’s model we saw earlier, or a reasonable facsimile. As you become more aware of your processes interdependencies with other parts of the organization, you may find you need something more sophisticated than Dr. Deming’s model, something my colleague Eric Budd explains in the following short vid:

Summary:

The aim for this entry was to get our feet wet in the first of six new leadership competencies that were introduced in our Nov 1st/23 newsletter. We’ve compared and contrasted the old view of train-wreck management that gave us the hierarchy model with the new view of production viewed as a system of interdependent parts and processes that are coordinated together to create products and services for a customer. From this, we gained an appreciation that no part works in isolation of others, with the consequence that changes in one part can affect many others, a key to understanding why the prevailing methods of management so often create more problems than they solve. We finally consider how, in light of this understanding, a systems view of leadership is qualitatively different from the hierarchical view.

Reflection Questions

What is the prevailing way you think about the causes of problems in your organization or others? What about your leadership or management? What effects have you observed? What relationships have you observed between how your organization may be structured with roles and departments with how it operates? What is the reaction to problems or mistakes? What is the primary disposition of managers? What are they most concerned with?

Consider Scholtes’ and Deming’s view of interconnectedness and the impossibility of isolationism: what implications does this suggest about how we predominantly think about the way we lead and manage organizations? Are we trying to ring-off things in world of systems?

Next Up:

Our next competency will be the ability to understand variability of work in planning and problem-solving…

Further Reading

Scholtes, Peter. The Leader’s Handbook.

Goldratt, Eli. The Goal.

Latzko, William J. and Saunders, David M. Four Days with Dr. Deming.

Neave, Dr. Henry. The Deming Dimension.