Concluding Episodes of Dr. Bill Bellows' Interview with Deming Institute

Ruminations on Quality, Variation, Gas Gauges, and the End of Perfection

Learning is what happens when things don’t go as planned.

When things don’t go as planned, we have an illusion of understanding.

Dr. Russell Ackoff as quoted by Dr. Bill Bellows

THE AIM for this newsletter is to share with you some brief highlights from the final three instalments of Dr. Bill Bellows’ interview with Andrew Stotz for The Deming Institute Podcast, “In Their Own Words”, that I first wrote about in my March 9th newsletter. In Episode #1, Bill shared how he began his Deming journey as a young engineer steeped in the the theory and teachings of the legendary Dr. Genichi Taguchi, and how he became bewitched after a serendipitous introduction to Dr. Deming’s philosophy by a training director at his office. Over episodes 2-4, Bill takes us deeper into his transformation into becoming a Deming thinker and practitioner as he explores questions about variation, quality, and continuous improvement.

These podcasts can also be found on The Deming Institute site (along with transcripts) here:

Here’s a sampling of what you can expect to learn from him as he explains his thinking about his thinking across the remainder of the podcast:

Question One/Question Two Thinking

It’s been my experience in knowing Dr. Bellows for several years that he has a penchant for explaining deep topics with dichotomies such as “Red Pen / Blue Pen” (or Me vs. We) companies to highlight those that think in terms of “meets specifications” and those that go beyond to how well the parts fit together (drawn from an exercise he created a number of years ago). His latest refinement of this thinking is in the form of two questions that characterize how “we” have thought about quality for over 150 years:

Question One asks: “Do the parts meet specifications or requirements: Yes/No?” It’s a binary view of the world that excludes variation, and one that predominates our world: White beads are good, red beads are bad; eliminate all the red beads. What the beads will be used for is not our immediate concern; we’ve done our job.

Question Two asks: “How well do the parts perform for their intended purpose?” This is a more nuanced view of the parts as an extension of the system that produced them, predicated on an understanding of variation: White beads are good, but not all white beads are the same, varying in color, dimension, drilled bores; their acceptability depends on what the beads will be used for. Improving quality depends on understanding the causes in the variation of acceptability of the parts or product.

Gas Gauge Thinking

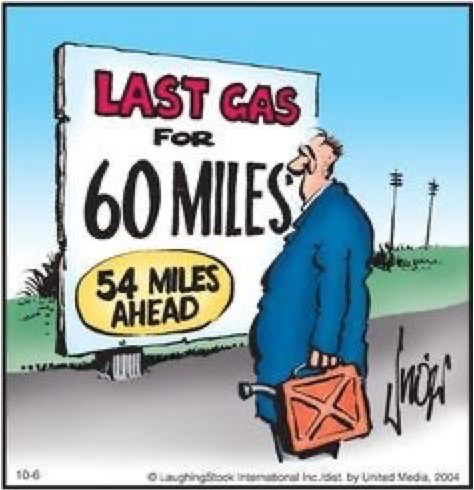

In The New Economics, Dr. Deming describes Management by Results (MBR) as one of the “faulty practices” of the prevailing style of management: “Take immediate action on any fault, defect, complaint, delay, accident, breakdown. Action on the last data point.” It is roughly analogous to how we manage our municipal infrastructure here in Toronto: Wait until it breaks.

The obvious question is: why do we wait for things to go wrong before we take action? Why don’t we take remedial steps when the costs are lower and the effort easier?

Bill frames this as the difference between reactive and proactive thinking, using the analogy of a gas gauge in a car: Reactive thinking is waiting to run out of gas before refuelling; proactive thinking is checking the gauge frequently to judge when to refuel based on the current situation. He asks us to consider whether we are as diligent in how we monitor the health of our systems, and in what ways we’re actively seeking out improvement opportunities with similar “gauges” to help avoid running out of gas.

Imperfect Perfection

In Episode #4 Bill will challenge your thinking about your thinking when it comes to understanding the different ways we use the word “perfect” in the context of “it’ll do for what I need right now” and “Perfection” as a Utopian end-point for continuous improvement efforts. He puts forward a controversial argument that by striving for “Perfection” (capital-P intended), we’re implicitly stating there is a point beyond which there is no further improvement to be made.

Reaching back to the Red Bead Experiment, he asks us to question our understanding of Deming’s philosophy: Is the aim of the simulation to have us think about eliminating all the red beads from our systems as achieving Perfection? What more is there to do, then? The answer is more profound than you might think.

Teamwork

Perhaps my favourite take-away from this series are the thoughts Bill has in Episode #3 on the implications of changing your thinking from “meets specifications, I did my job” to “how well does the part fit the context, and how can I help you?” with respect to enabling teamwork. By simply paying attention to how others use your work, a little up-front effort on your part to design it well for the next person can make their life a lot easier and reduce the time and friction required to become productive rather than struggling through compensating rework cycles.

How can you prevent mistakes (either overt or implicit) from being passed along?

Can you anticipate how the work could be misused? How could this be prevented?

Can visuals be used to better communicate complex or easily misunderstood information?

Would it help to consolidate many disparate parts into one whole?

Reflection Questions

Consider the proposals about quality, variation, teamwork, reactive/proactive thinking, and Question One/Question Two thinking Dr. Bellows puts forward in his interview series with Andrew Stotz:

How often do you consider the downstream consequences of your actions and decisions at work? Are your processes and workflows designed to “meet specifications” and cause reactive thinking?

In what ways do you currently think about how your work will be used by others in your organization?

Can you identify any instances where a lack of consideration for downstream impact has led to inefficiencies or problems in your work or projects? In what ways?

Have you observed any examples of successful teamwork where individuals consistently think about how their work affects others?

How might adopting a more collaborative and systemic mindset improve teamwork and overall performance in your organization?

What barriers or challenges might prevent you or your organization from thinking and acting together vs. as parts? How could they be overcome? Where would you begin?

How many “gas gauges” do you have in your organization to monitor the health of systems and processes to catch and prevent small problems from becoming big problems? How would you design some for the processes you use right now?