Chain Reaction

Quality, Productivity, Lower Costs, Capture the Market

Some folklore. Folklore has it in America that quality and production are incompatible: that you can not have both. A plant manager will usually tell you that it is either or. In his experience, if he pushes quality, he falls behind in production. If he pushes production, his quality suffers. This will be his experience when he knows not what quality is nor how to achieve it…

A clear, concise answer came forth in a meeting with 22 production workers, all union representatives, in response to my question: “Why is it that productivity increases as quality improves?”

Less rework.

There is no better answer. Another version often comes forth:

Not so much waste.

Quality to the production worker means that his performance satisfies him, provides to him pride of workmanship.

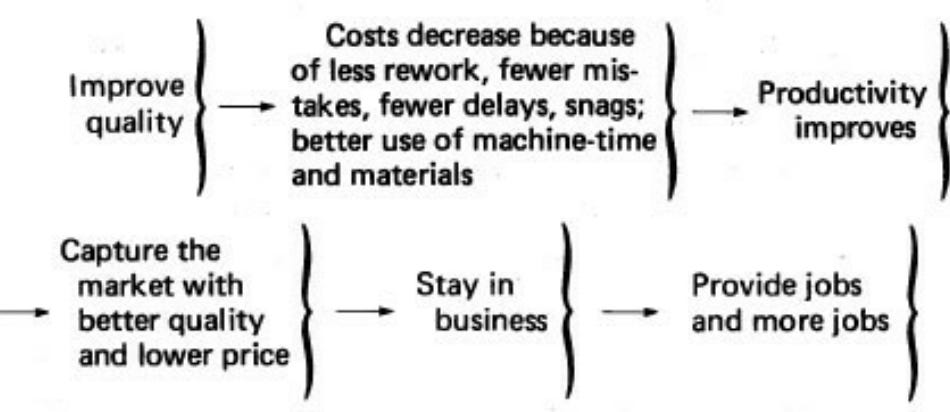

Improvement of quality transfers waste of man-hours and of machine-time into the manufacture of good product and better service. The result is a chain reaction—lower costs, better competitive position, happier people on the job, jobs, and more jobs…

This chain reaction was on the blackboard of every meeting with top management in Japan from July 1950 onward… Once management in Japan adopted this chain reaction, everyone there from 1950 onward had one common aim, namely, quality.

With no lenders nor stock holders to press for dividends, this effort became an undivided bond between management and production workers.

- Deming, W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis (MIT Press) (pp. 1-2). The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

Chain reaction. Improve quality, what happens? Your costs go down. Half the people here will understand that. The other half will not… I want to make it clear that as you improve quality, your costs go down. That is one of the main lessons that the Japanese learned and that American management doesn’t even know and couldn’t care less about…

You can talk about quality, but if you don’t know what to do about it, bring it about, quality is an empty word.

- Dr. W.E. Deming as quoted from one of his four day seminars by Walton, Mary. The Deming Management Method. (pp. 25-27)

THE AIM of today’s post is to share the elementary “secret” that Dr. Deming taught the Japanese that set their war-ravaged industries on a path to conquer the world’s markets with high quality, lower priced products. It is just as valid in our time, and I think just as ignored now as it was up until the 1980s when Deming was rediscovered thanks to the NBC Whitepaper documentary, If Japan Can, Why Can’t We?I think there is just the same sense of urgency that something has to change because it is clear the standard management ways are no longer sufficient for what we must do.

Below is a rendering of the diagram Dr. Deming’s “chain reaction” from Out of the Crisis that would be on every blackboard for every meeting with top-management that he would have. It is the on-ramp to understanding how Deming viewed production as a system, and the thread that runs throughout:

According to this roadmap, any investment that is not directed at improving quality directly is an investment wasted. This is the adoption of the new philosophy that Deming advocates in Point #2 of his 14 Points for Management; observe the connection he makes between how society works and the organization - this is a plan for restoring a nation:

2. Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age, created by Japan. Deadly diseases afflict the style of American management (see Ch. 3). Obstacles to the competitive position of American industry created by government regulations and antitrust activities must be revised to support the well-being of the American people, and not to depress it. We can no longer tolerate commonly accepted levels of mistakes, defects, material not suited for the job, people on the job that do not know what the job is and are afraid to ask, handling damage, antiquated methods of training on the job, inadequate and ineffective supervision, management not rooted in the company, job hopping in management, buses and trains late or even canceled because a driver failed to show up. Filth and vandalism raise the cost of living and, as any psychologist can aver, lead to slovenly work and to dissatisfaction with life and with the workplace.

Deming, W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis (MIT Press) (pp. 26-27). The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

Improving the quality of any product or service, anywhere, is thus the key to freeing up time and capital that in turn enables capturing of markets and boosting profits. This perspective, contrary to the prevailing wisdom in North American industry, was also shared by Dr. Eli Goldratt, whose Theory of Constraints as explained in The Goal is predicated on the freeing-up of capacity in an organization that is locked behind a network of constraints. As he observed, “an hour lost on the bottleneck is an hour lost for the entire system”.

Below is a rendering of the chain reaction as a Causal Loop Diagram I made based on a schematic I found some time ago - it makes the “system” of thought a little more clear, as a virtuous cycle, as opposed to the vicious cycle of cost-cutting and layoffs that seem to predominate businesses and organizations, once again.

(s) indicates “moves in the same direction”, (o) indicates “moves in the opposite direction”. As Quality improves, so does Customer Satisfaction and Productivity. As Productivity increases, Prices and Costs decrease. As Costs decrease, Profits increase. As Prices decrease, Market Share increases. As Customer Satisfaction increases, so does Market Share, and ultimately Profits.

Begin Improving Quality Now

An old proverb tells us the best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago, but the second-best time is now. Anyone can begin to improve quality anywhere right now. You are at the top of something, irrespective of your job or role, and can choose to make a difference by changing something small about your own perspectives and thinking that then leads to improvements in how you carry out your tasks. There are spheres of influence you begin with, which may be small, that then expand as you influence others - it can be contagious.

Quality in education expert, David Langford, tells a story of how he began his journey after returning to his school from a Deming four day seminar, ready to begin the big work of improving quality only to be shut-down by the governing school board who viewed his ideas as too radical. Defeated, he returned to his classroom and had an epiphany that this was his current largest sphere of influence. He decided to ask his students what he was getting wrong, in their judgment. He got an earful, but it was a goldmine of things he could begin to work on immediately. From this beginning, he went on to change an entire school. You can see the effects in this short documentary on The Deming Institute site.

Reflection Questions

Choose something that is a source of repeated frustration or dissatisfaction for you in your work or even your own habits: Examine and study for why it is so. What are the contributing factors? How are they categorized? What influences them? How many can you directly influence? How many can you influence with the help of others? What gains do you anticipate from improving one or more of them? What does the operational data tell you today? Can you plot a run-chart with process limits to know whether your system is reliably unreliable (stable) or randomly failing (unstable) ?

Have we become complacent with respect to quality? Are we under the belief that quality costs more, or that there is a limit to how far we can improve quality before it costs more than it’s worth? Are we captured by the folkloric wisdom Deming saw decades ago? Do we care about profits? What evidence do we have that we understand and implement Deming’s Chain Reaction, de facto or de jure ? If we understand the chain reaction, why are we not doing it? If we did it then, why can’t we do it now?